Hello AI Agents: Goodbye UI Design, RIP Accessibility

Summary: Autonomous agents will transform user experience by automating interactions, making traditional UI design obsolete, as users stop visiting websites in favor of solely interacting through their agent. Focus on designing for agents, not humans. Accessibility will disappear as a concern for web design, as disabled users will only use an agent that transforms content and features to their specific needs.

Once, humans navigated the web manually. In the future, AI agents will act on our behalf, browsing, clicking, and deciding. This shift marks the end of traditional UI design and accessibility, ushering in a future where agents are the primary users of digital services.

Late 2024 and early 2025 saw the emergence of AI reasoning models like DeepSeek R1 and OpenAI Deep Research (together with Google’s product of the same name and xAI’s “Big Brain” feature). However, the main new development for 2025 is expected to be agents, including OpenAI’s Operator, Claude’s “Computer Use,” Microsoft’s Copilot agents, and Google’s Gemini Assistant.

Definition of an AI agent: an autonomous system that performs tasks or makes decisions on behalf of users, such as browsing the web or controlling a computer, without needing constant human input, distinguishing it from chatbots that require prompts to act.

Watch my video: AI Agents Explained in 5 Minutes (YouTube).

Thus, an AI agent is a computer program that can sense information, make decisions, and act on its own to accomplish a task. It’s an entity powered by artificial intelligence that operates with some independence, whether it’s a virtual assistant on your phone (like Siri or Alexa), a character in a video game that acts intelligently, or a system to surf the web and take action on your behalf. Advanced agents will learn from experience and improve their responses over time.

AI agents will take actions on behalf of their user, partly based on aggregating information across many sources that they seek out on their own. (Ideogram)

Current AI agents demonstrate a variety of capabilities: OpenAI's Operator can handle web-based tasks like filling out forms, ordering groceries, and booking travel by interacting with web pages through its own browser. Anthropic’s Computer Use allows their AI to control a computer directly, and Microsoft's Copilot agents focus on automating tasks such as triaging emails and managing expenses.

Looking ahead, AI agents are expected to evolve significantly, taking on complex tasks across industries like customer service, healthcare, and education, and even operating at Ph.D. level to carry out research studies. Such “service as software” agents will transform economies by automating high-level work. However, these agents are still in their early stages, with limitations like occasional errors and safety concerns that require further development before they’re let loose.

Main Current AI Agents

Existing popular products like Deep Research can be considered as simple agents in their own right, even if they are not positioned as such. These research tools browse the web and search databases on behalf of the user. They go beyond simply fulfilling a query (as a traditional search engine like legacy Google or even an answer engine like Perplexity would do) and take their own initiative to investigate the user’s problem in more depth than was specified in the initial request. The main reason they aren’t true agents is that they currently don’t take autonomous action on the user’s behalf.

5 different AI agents from major providers are already competing to manage the users’ tasks for them. The table shows an overview, but more will probably join the fray soon. (Leonardo)

As a good example, I asked Deep Research to make a comparison table of the main current agents, showing their main properties. I didn’t specify which tools to include or which agent properties to show. Here’s the result:

OpenAI “Operator” (Research Preview)

Goal-directed autonomy for single tasks; iterates steps until done, but will pause for user help if stuck or for safety. Human confirmation needed for sensitive actions.

Integrated with a built-in web browser (can click, type, scroll on websites). Plans and acts within web environments. Limited to on-screen actions (no direct OS control beyond browser).

Vision + Text: Interprets web page images/text (via GPT-4’s vision). Generates text (for forms, chats). No native speech or audio; not known to generate images (aside from editing existing meme templates).

Online tasks and “digital errands”: e-commerce (shopping, ordering food), form filling, account sign-ups, travel bookings, web research aggregation. Acts as a web assistant to automate routine internet workflows.

Google Gemini Agents (Google DeepMind)

High-level autonomy with oversight: Can handle multi-step tasks and make suggestions, but designed to work with user supervision. Likely to ask for permission on critical actions.

Deep integration into Google ecosystem: Search, Gmail, Docs, Maps, etc. Can call Google’s tools/APIs (e.g. use Maps to check traffic, use Gmail to send an email). Also has a code execution sandbox (for coding agent) and web navigation abilities via Chrome.

Multimodal (text, images, audio, possibly video): Native image understanding and generation, text generation, and limited audio (text-to-speech and speech-to-text in Assistant). Plans to integrate vision (Google Lens) and voice (Assistant) fully.

General-purpose assistant across devices. Examples: answer questions with combined text/image results, plan events (pulling info from calendar, maps), control smart home or phone (via Assistant), generate content (emails, documents, illustrations). Specialized agents for coding (writing & debugging code autonomously) and data analysis (analyzing data, creating charts). Aimed at both consumer convenience and professional productivity.

Anthropic Claude with “Computer Use”

Extended autonomy on PC tasks: Can perform long sequences (dozens of steps) on its own. Still marked experimental — will hand off to user if it encounters unsupported scenarios or errors. It likely requires the user to initiate and define goals, then observe/step in if they falter.

Works via virtual computer interface: through API, it controls a headless browser or OS simulator (moving cursor, clicking, typing). Can interface with web apps and possibly desktop apps (for now, primarily web). No deep OS integration has been announced; focus is on web-based software workflows.

Vision + Text: Can “see” the UI (screen pixels to text) and read documents. Strong text generation and understanding. No inherent image generation or audio features in Claude’s public versions.

Work automation and complex online workflows: e.g. log into enterprise SaaS, fetch data, cross-post into another system; customer support tasks (read an email, open database, update record); personal chores like booking appointments online. Also excels at large-scale text processing (editing documents and summarizing multiple sources) thanks to a huge context window. Designed to augment knowledge workers, handling multi-app procedures (with an emphasis on business use cases like project management, software QA, etc.).

Meta AI Assistant (powered by Llama 2/3)

Conversational, on-demand autonomy: Responds to user requests and can take initiative within a conversation (e.g. it might offer to set a reminder), but does not execute unattended long sequences on external sites. Essentially one-task-at-a-time, under continuous user interaction.

Integrated in Meta’s apps (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger). Can retrieve real-time info via search integration. Can generate images via Meta’s generative image model. Not integrated to perform actions in other external apps (no direct web control or IoT commands yet).

Multimodal (text, images): Understands text prompts, context of a chat, and has some image understanding (e.g. you can send it a photo to get a description). Can output images (quick GIFs, photorealistic pics) and text. No voice interface at launch (relies on typing), but can be used in messaging apps that support audio notes (future voice possible).

Consumer/general assistant: answering questions, providing recommendations (like a smarter search engine in chat form), helping with creative tasks (writing social media captions, stories), and entertainment. For example, acts as a planning buddy (“What should I do in London for 3 days?”), a study helper (“Explain quantum physics in simple terms”), or a creative partner (“Write a funny caption for this photo”). Also generates custom visual content (stickers, stylized images) on request. Integrated into social/family use cases rather than executing business processes.

Microsoft Copilots (Windows/Office)

Assistive autonomy: Works in a loop of taking user instruction, performing a set of actions, then awaiting further input. For instance, it might draft a document and wait for user edits. It automates multi-step tasks within applications, but not wholly on its own (user typically triggers each high-level task).

Embedded in software tools: e.g. Office Copilot has deep hooks in Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook. It can command these apps to create or modify content (using internal APIs). Windows Copilot can change OS settings or open apps. Also has access to third-party plugins (e.g. Bing plugins for external services). Not a free-roaming web agent by default — acts within the confines of known apps/services for reliability.

Primarily text: Excellent natural language understanding and generation (powered by GPT-4). Limited vision (e.g. can generate descriptions from images in PowerPoint or parse a screenshot using an add-on, but not a core feature yet). Can produce formatted outputs (Excel tables, slides with design) — a form of multimodality within productivity content. Supports voice input/output through Cortana/Assistant in Windows (in limited capacity).

Productivity and office tasks: drafting emails, summarizing documents, creating presentations, analyzing spreadsheets via natural language queries. In Teams, it can recap meetings and action items. In Windows, acts as a system assistant (toggle settings, answer questions by searching the web). Essentially a supercharged Clippy for the modern era — focused on helping users get work done faster, maintaining context across Office apps. Also useful for coding within Visual Studio (as GitHub Copilot, it writes code suggestions).

AI agents exist at many levels of sophistication. The highest level of autonomy may not arrive until 2030, at least for sensitive use cases. (Napkin)

History of Agents

Rule-Based Beginnings (1950s–1980s): The concept of an “AI agent” traces back to early AI programs and theories. Pioneers like Marvin Minsky imagined intelligence as emergent from many smaller agents (his “Society of Mind”). Early agents were largely rule-based or expert systems designed for narrow tasks. While they could follow predefined rules, they lacked true understanding or adaptability. For example, 1980s expert systems could diagnose diseases or configure products, but only within rigid parameters. These systems were brittle and failed when encountering scenarios outside their rules, and they couldn’t learn from experience. This limited their real-world impact, and enthusiasm waned as the second “AI winter” hit in the late 1980s when progress stalled.

1990s “Intelligent Agents” Hype: In the 1990s, researchers and companies became excited about “intelligent software agents” in the form of programs that would autonomously assist users (like scheduling meetings or filtering emails). Multi-agent systems (collections of agents) were also explored, hoping they could collaborate or negotiate. One famous example was General Magic, a startup that envisioned personal digital assistants performing tasks for users. However, the technology wasn’t ready: devices were underpowered, and the agents themselves failed to deliver results, causing interest to fade. A well-known attempt from this era was Microsoft’s Office Assistant “Clippy” (1997) — essentially an early UI agent. Clippy tried to anticipate users’ needs (e.g. offering help writing a letter) but it had very limited intelligence. It often misunderstood user intent and became an industry joke rather than a helpful aide. The promise of 90s agents largely fizzled because AI was too primitive: natural language understanding was poor, and these agents couldn’t truly reason or learn, leading to a loss of interest in the area for another two decades.

2010s Virtual Assistants: In the 2010s, mainstream “AI agents” took the form of voice-activated assistants and chatbots. Apple’s Siri (2011), Google Assistant (2012 as Google Now), Amazon’s Alexa (2014), and Microsoft’s Cortana (2014) brought the idea of a digital personal assistant to millions of users. They could handle spoken commands to do simple tasks like setting reminders, playing music, or answering fact-based questions. While popular, their impact was limited to convenience tasks, because the usability was too limited for users to make the agents do anything sophisticated. I personally had Alexa for about a year but almost exclusively used it for the weather forecast and to set timers. These systems were not really agents but voice-controlled command interfaces that would not take autonomous action on the user’s behalf.

Why Earlier Iterations Fell Short: Across these historical efforts, a common theme is that the agents were too limited to make a major impact. Early systems could not truly understand context or handle unpredictability. They lacked memory of past interactions and had no genuine reasoning ability. If a task deviated from what they were explicitly programmed to do, they’d either give up or produce nonsense. Voice assistants, for instance, couldn’t hold multi-turn dialogues or perform complex sequences: any error would derail the process, requiring the human to step in. Essentially, earlier “agents” were not autonomous problem-solvers but collections of narrow skills. They also tended to be siloed (a chatbot couldn’t control your calendar unless specifically integrated). This meant they augmented human workflows in small ways but couldn’t automate truly open-ended tasks. The primitive pre-ChatGPT AI used simply wasn’t powerful enough for the grand vision of an all-purpose digital helper, so those early agents remained novelties or niche tools instead of transformative platforms.

AI agents have progressed through many false starts but are finally getting to be real. (Napkin)

Why Now?

The historical limitations have finally been overcome. Not to the extent that the agents of 2025 can do everything envisioned in the 20th Century’s dreams of autonomous computer agents. But current AI does understand context; it can read your computer screen, and it has multi-modal capabilities, allowing it to act across formerly separate applications. (Even my simple comparison table at the beginning of this article was compiled across 35 different sources, each of which had its own way of presenting information, which Deep Research spent 38 minutes on extracting and then compiling into a uniform format.)

As always with AI, the question is not the tools' current capabilities, but the progress rate and what that means for their capabilities in a few years. For example, one user posted a breakdown (with screenshots) of trying to get OpenAI’s Operator agent to file his expense report, and while it completed some steps fine, it could not complete the full task. He concluded that the current agent was fine for narrow tasks or tasks where perfection is unimportant.

This small case study should not make us conclude that AI agents will never be able to complete medium-sized tasks (like an expense report) or large tasks, or that they won’t be able to perform tasks where precision is required (like any financial task). Two years from now, we’ll have the next generation of AI, which will have better skills, and in 5 years, almost all the problems will be solved. Maybe it’ll be 10 years before we AI agents routinely file most people’s tax returns, but completing expense reports is well within reach in less than 5 years.

For example, people have already established Deep Research agents that scan the news each morning and create a daily summary newsletter optimized for that individual user’s interests, no matter how obscure. No more visits to newspaper websites for those users. (Though in the future, I could imagine a few news organizations being sufficiently good that users would pay a small subscription fee for their agents to be allowed to access their news feeds. Almost certainly, those subscriptions will have to cost dramatically less than the current price of accessing an entire newspaper website.)

Today’s agents perform best in fairly structured, digital domains: web browsing, form-filling, code-writing, etc. They are less capable in the physical world (though some robotics-integrated agents exist in labs). If a task involves interacting with the real environment in unpredictable ways (e.g., a home robot or a complex negotiation), current AI struggles due to a lack of real-world grounding or long-term planning stability. Experimental robot agents like Google’s RT-2, where an AI-controlled robot uses vision and language knowledge to pick objects, are not consumer-ready.

Realistic use cases currently center on the digital realm: organizing information, automating online processes, analyzing data, and generating content. In the digital domain, AI agents do provide significant speed-ups (e.g., drafting a lengthy report would take humans hours, but an AI agent can assemble a decent draft in minutes). But they are not reliably better than humans at complex decision-making and are currently best used as tireless assistants to handle grunt work under supervision.

I expect that by 2027, many professionals will have semi-autonomous AI helpers at work (drafting emails, scheduling, researching), and power users will start delegating bits of personal chores to AI (maybe your AI can reschedule your appointments or sort through your photos). The truly transformative agent — an assistant that you trust unreservedly — will likely emerge gradually as the tech and our confidence in it mature. True personal assistants may have to await the expected arrival of superintelligence in 2030.

AI agents work tirelessly on behalf of their users. Currently, agents excel at retrieving and analyzing copious amounts of disparate data sources. In contrast, we may have to wait a few years until an agent routinely takes action on the user’s behalf. (Leonardo)

How Current Agents Work: OpenAI “Operator” Case Study

OpenAI’s Operator was introduced as a research preview in early 2025. It’s a version of ChatGPT that can operate a web browser to perform tasks for the user. Rather than just giving answers, Operator can click, scroll, and type on websites automatically. OpenAI describes it as an agent for “repetitive browser tasks such as filling out forms, ordering groceries, and even creating memes”.

In demos, Operator was told to fetch a pasta recipe and order the ingredients online, and it successfully navigated AllRecipes, then Instacart, to complete the entire order. In another example, it planned a trip via a travel site. Under the hood, Operator runs on a new model called the Computer-Using Agent (CUA), a variant of GPT-4. This model combines GPT-4’s advanced language reasoning with vision capabilities to understand what it sees (it looks at webpage screenshots) and with training to manipulate graphical user interface elements.

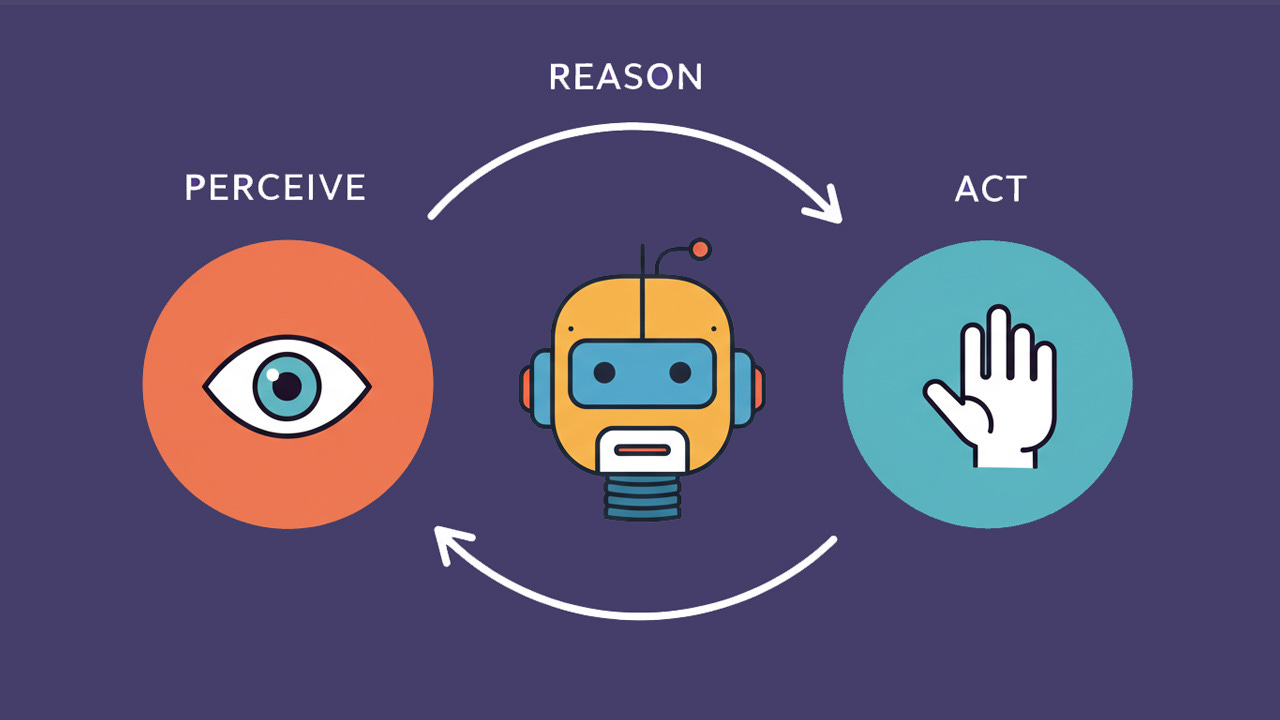

Operator functions in iterative loops of perceive → reason → act. It “sees” the current webpage (through GPT-4’s vision, interpreting the screen like an image), internally plans the next action, and then executes clicks or keystrokes. It continues this loop until the task is done. For instance, if asked to book a restaurant, it could navigate to OpenTable, search for the restaurant, pick a date, fill in details, etc., step by step.

The 3 steps of an autonomous AI agent. Note that after the agent has acted (e.g., clicked a button on a website), it starts the process over by perceiving the new state of the system (e.g., website) it’s operating. (Imagen)

Importantly, OpenAI has built in safety guardrails: Operator will pause and hand control back to the user when certain sensitive steps arise. It refuses high-risk tasks like financial transactions, and if a login or password is required, it asks the user to intervene and enter credentials manually. This means Operator is not entirely free-roaming — it’s constrained to avoid costly errors or abuses.

(Obviously, for AI agents to be truly useful in performing tasks on the user’s behalf, they will need full access to his or her passwords, maybe with limits enforced for the amounts of money the agent can spend on behalf of its user.)

Operator is aimed at automating tedious online chores. OpenAI specifically mentions tasks like vacation planning, filling out forms, making restaurant reservations, and online shopping. In an enterprise context, it could handle repetitive web-based workflows (e.g. data entry across web portals). Essentially, it serves as a personal web assistant or a prototype of a “universal UI” that uses the same websites humans use.

Currently Operator is only available to US users with ChatGPT Pro ($200/month) accounts — a sign that it’s still early-stage and being tested in limited rollout.

Compared to earlier agents, Operator’s strength is reliability in executing multi-step web tasks. It leverages GPT-4’s intelligence for deep reasoning and understanding of instructions, combined with actual GUI manipulation. This is far more sophisticated than the single-turn commands of Siri/Alexa. One observer noted that Operator “demonstrates reliability in ways we have not seen from… frontier model providers” when it comes to following through on tasks.

Its ability to see the interface is also key; unlike text-only bots, it won’t get lost on a webpage because it can read the buttons and text on the screen. However, OpenAI intentionally limits Operator’s autonomy (it’s cautious, requiring confirmations), which, as testers have found, means it’s not yet a hands-free concierge for everything. OpenAI currently frames Operator as a “research preview,” implying it’s a stepping stone toward more capable autonomous agents in the future as they continue to improve the model’s deep reasoning and expand its action space.

Agents Replacing UI Design

The best current agents (e.g., OpenAI Operator) can take over your computer, read information on the screen, understand it, plan the necessary next step, and execute actions to achieve this step, such as typing information into text-entry fields and clicking buttons and menus. This sounds a lot like a description of a person using a user interface to accomplish a task, and that’s exactly what it is.

Instead of having a human interact with your UI, in the future, it’ll be an AI agent using your UI on behalf of its human. At the limit, human users will vanish from the web and many software applications.

A likely scenario is that the “user” only interacts with his or her agent, and the agent then performs any specific interactions with the services needed to accomplish the tasks the agent was ordered to perform.

My comparison table at the beginning of this article is an example: I didn’t visit any websites from the agent providers or where agent reviews had been published. Deep Research made all these visits for me and then extracted the information it deemed relevant from all those web pages it visited. (To be precise, I did click a few of Deep Research’s citations to double-check a few matters, but mainly, I never saw the 35 websites it visited.)

Once the transition to agents has been completed, websites may never see a human user again. This means that UI design, as traditionally conceived, becomes irrelevant. Look and feel? Bah, nobody will care whether it looks nice or ugly or how it feels to use your website since no (human) will be using it.

Other aspects of user experience will remain. For example, you’ll still need to design the features that are required to support user tasks, though workflows might have to be reconsidered once they are exposed to AI, as opposed to having to be easily understood by humans.

The same is true for content design (AKA, writing). Nobody will be reading web pages. Instead, the AI agent will extract the information it wants to present to its user and rewrite it in the style it knows the user prefers. This will include rewriting information at a readability level appropriate for the user’s IQ and education level.

(This article is written at an 18th-grade reading level, corresponding to a master’s degree, since that’s the approximate level of most of my subscribers — whether or not they have the degree, they have the IQ, or they wouldn’t be here. But an AI agent could simplify the exposition to be easily understood by a high school dropout.)

In the ultimate scenario, the only design consideration for digital services (whether offered through the web or as software applications) becomes to cater optimally to AI agents. No humans will interact with the design, so the traditional “user interface” will vanish.

How do you project a brand through the intermediary of an agent? Photography and other illustrations will remain important even as the layout disappears. Some remnants of writing style might also be retained in some of the agent rewrites and summarizations. But the main point will be to provide the information that agents deem important to show to their humans.

The web is about to reach the end of a 30-year period where SEO (search engine optimization) was the main driver for website visibility and visitor count. In many ways, it was more important to write for GoogleBot and other crawlers than for humans. So optimizing website content for AI agents is not a truly new venture, even though the specific guidelines will no doubt be different. You want to rank highly in the agents — that’s the new imperative for business survival.

The Transition Period: Some Humans, Some Agents Visiting Websites

Some people have questioned why we should even have websites if all user actions happen through agents, whether people are pursuing research, entertainment, or transactions. Why not expose all the information to the AI services through an API and be done with it?

One reason to retain websites for at least 10 more years is that there will be a transition period, where some early adopters will be using agents, and the laggards will continue to browse websites manually. During this period, you must cater to both humans and agents.

The transition period has already started! Deep Research and similar agents already account for some percentage of website visits. A study of 3,000 websites in February 2025 found that 63% of them had received visits from AI agents, with 98% of AI traffic deriving from only 3 agent providers: ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Gemini. (Not to say that other agent providers can’t become important later, but right now, if you want to optimize your website for agents, start by considering these three.)

In February 2025, the average website only had 0.2% of its traffic from AI agents, though this estimate may be too low, because not all visiting agents disclose their nature accurately. Interestingly, in this study, smaller brands received more AI traffic than larger brands as a percentage of total traffic. This finding makes sense, because a human will typically limit his or her browsing to a few top sources, whether brands that are already known (mainly big brands) or brands that rank high on a SERP (search engine results page, again the haunt of mostly big brands). In contrast, an AI agent will usually explore further in its quest to solve a problem.

I welcome the extent to which AI agents can revive the original ideal of the web as the home for a large number of voices (including my own modest UX Tigers website), as opposed to being dominated by a few megabrands and tech giants.

Most likely, there will be a slow transition where AI agents gradually account for a bigger percentage of a website’s value. Will human visitors ever disappear completely? That remains to be seen, but I could easily see this happen eventually.

During the transition period, a website will receive a mix of visits from human users and from AI agents acting on behalf of other customers. Over several years, the mix will gradually switch in favor of more agent visitors. (Leonardo)

One of the reasons I believe that the current generation of AI agents will kickstart this transition is that they are capable of being useful even while current websites are designed purely for human visitors. Current AI can see web pages, read the text, and interpret the images. They might perform optimally with differently-encoded information, but they’ll work just fine right out the gate.

This ability of AI agents to work with human-targeted design is a major contrast to previous attempts to build “the semantic web” and other machine-readable versions of Internet content. There was a major chicken-and-egg problem where companies were requested to invest substantial resources in building these new content resources even as almost no customers were employing them to do business. (And conversely, users never adopted software that was useless as long as virtually no content-providers had provisioned information in the new formats.)

RIP Accessibility, Agents Will Help Disabled Users Better

Since the first web accessibility guidelines were published in 1999 (and I wrote a chapter about accessibility in my book Designing Web Usability, published the same year), it’s been the hope that better coding of web content and features would help disabled users use websites better. This hope has failed. Usability for disabled users remains unacceptable, mostly because encoding mechanisms is an underpowered approach to task support.

A year ago, I thought that Generative UI was the solution to this problem. Instead of encoding the same web page to supposedly work for users both without and with functional limitations, we would use AI to generate separate user interfaces for each class of user. For example, blind users would get a fully auditory user experience that was designed as such. This would offer superior usability compared with the accessibility approach of first designing a 2-dimensional graphical user interface for sighted users and then ensuring that it could be linearized and read aloud. (Something that never worked.)

I still believe that Generative UI could vastly increase usability for disabled users. Besides the example of generating a first-class auditory UI, it could also generate rewritten versions of all content for low-literacy users who need text written at an 8th-grade reading level.

However, this use of Generative UI to serve disabled users better is now likely to only be a placeholder solution while we wait for better AI agents. We’ll get these agents by 2027, or by 2030 by the latest. For the sake of helping disabled users, I think 2027 is the more likely target year, for two reasons. First, disabled users are highly motivated to get a better user experience than the misery they suffer currently, so they’ll be early adaptors and will be willing to use semi-autonomous agents at first, even if they require more human hand-holding than a non-disabled user would be willing to provide. Second, much of early agent use by disabled users will be non-critical, such as reading the news and social media or placing ecommerce orders, which can be confirmed before payment and redone if needed. (In contrast, it’ll likely be 2030 before we let agents lose on the Internet with permission to wield our credit cards autonomously.)

Assuming that disabled users will mainly turn to agents for their Internet use starting in 2027, there’s not enough time available before then to develop high-capability Generative UI and embed it in enough websites to matter.

Thus, I no longer believe that Generative UI is the solution to poor accessibility. Instead, AI agents are the answer.

Accessibility is close to dead. As soon as most disabled users embrace AI agents for their Internet needs, websites can focus on serving agents, knowing that this will optimize the user experience for all users, regardless of any disabilities. (Leonardo)

The agent can browse the web on behalf of the user and see the web pages as they are designed to be seen, even if its user is blind. The agent can also click and slide any GUI elements as intended, even if its user has motor skills impairments. And the agent can read and understand content at any readability level, even if its user has low literacy skills — or is even illiterate. The agent can do all this and then communicate with its user in ways that are optimized for that user’s capabilities, needs, and preferences.

Disabled users will also be motivated to spend time teaching their agents about their preferences, and unique requirements, reducing the need for the agent to be smart enough to infer these on its own, as it will likely have to do for most users who are less motivated to spend time setting up an AI agent.

Agent Usability and Design Guidelines

Since general AI agents have only been available for a few months (and only in preview versions for the more capable general-purpose agents, at that), I could not find any real usability studies of people using agents for real tasks.

There are some studies of limited agents that partly automate certain tasks, such as partly self-driving cars where human drivers are supposed to be available to take over at any time. The main finding is that trust in the semi-agent system builds slowly and plummets when it makes a mistake. Also, users easily misinterpret the agent’s true capabilities, partly because overly eager marketing statements can mislead them. (A good example of the fact that the way a system is promoted becomes part of the total user experience by setting user expectations.)

Trust builds slowly, especially for critical business applications where the user’s job (or company) is on the line if the agent goofs up badly enough. In the beginning, the user will likely monitor the agent closely and gradually ease up as the agent proves itself. (Ideogram)

These findings lead me to a general guideline that it’s probably best to go slow with introducing agents for important tasks. In general, I am very gong-ho about accelerating AI use, but that’s in cases where AI works with humans. For autonomous agents that work on the user's behalf, we should ensure that AI has advanced to a stage where the agent will perform the task correctly a very high proportion of the time due to the adverse impact on user experience when it fails.

A general guideline for AI agents is to treat them like a donkey-pulled cart: go slow and only put as much in the cart as the donkey can pull. (Midjourney)

The following initial design guidelines for AI agent user experience are partly based on the time-proven 10 usability heuristics. Since they embody the most basic principles for interaction between humans and machines, they will also apply to AI agents.

Set Clear Expectations Up Front: Ensure users know what the AI agent can and cannot do before they start using it. Clearly communicate the agent’s capabilities, scope, and limitations. By being honest about limitations, designers can prevent the user from forming unrealistic mental models. This includes using straightforward branding and names that avoid exaggerated terms to not overinflate expectations.

Match the Agent’s Behavior to User Context and Norms: AI interactions should be timely, contextual, and polite. An agent must pick the right moments to intervene or notify (e.g. not interrupt a user’s meeting with a non-urgent update). Agents should also follow social expectations: for conversational AI, use tone and language that fit the user’s cultural context. (Heuristic 2, match between system and the real world.)

Provide Transparency and Explainability: Whenever an AI agent makes a significant decision or recommendation, offer an explanation or at least make the reasoning traceable. Users should be able to get an answer to “Why did it do that?” This could be through an on-demand explanation UI or simple language justifications to help users calibrate their trust and double-check critical outputs. (Heuristic 1, visibility of system status.)

Support User Control and Easy Escapes: Always give users a way to correct the AI or opt out of its assistance when needed. This includes easy invocation and dismissal of the agent (e.g. a prominent “cancel” or “turn off” button) and efficient error correction mechanisms. If an AI is automating a task, let the user review and confirm critical actions (a confirmation dialog) or undo them after the fact. (Heuristic 3, user control and freedom.)

Handle Errors and Uncertainty Gracefully: Anticipate that the AI will sometimes be wrong or unsure, and design the UX to cope with this gracefully. This involves error prevention (don’t attempt actions with low confidence if the cost of failure is high), error messaging, and recovery options. Importantly, don’t leave the user stranded — always suggest a next step if the agent can’t handle the request. (Heuristic 9, help users recognize, diagnose, and recover from errors.)

Enable Feedback and Learning Loops: Treat users as partners in improving the AI agent. Provide channels for users to give feedback, such as a thumbs up/down on a recommendation, a short survey after an interaction, or a way to report “this answer was wrong.” (Such feedback can feed reinforcement learning to improve future releases of the agent.)

Learn from user behavior over time in a transparent way. Personalization can enhance UX (e.g. a task assistant learning a user’s preferences), but it should happen with the user’s awareness and control. For example, a scheduling agent could tell a user “I’ll remember your preference for morning meetings.”

I know I sound like a broken record, but even a broken record is right twice a day: you must conduct usability testing on any AI agent design. Since these are new user experiences, we can’t count on getting them right purely based on general usability guidelines like those listed above. (Leonardo)

Watch my video: AI Agents Explained in 5 Minutes (YouTube).

About the Author

Jakob Nielsen, Ph.D., is a usability pioneer with 42 years experience in UX and the Founder of UX Tigers. He founded the discount usability movement for fast and cheap iterative design, including heuristic evaluation and the 10 usability heuristics. He formulated the eponymous Jakob’s Law of the Internet User Experience. Named “the king of usability” by Internet Magazine, “the guru of Web page usability” by The New York Times, and “the next best thing to a true time machine” by USA Today.

Previously, Dr. Nielsen was a Sun Microsystems Distinguished Engineer and a Member of Research Staff at Bell Communications Research, the branch of Bell Labs owned by the Regional Bell Operating Companies. He is the author of 8 books, including the best-selling Designing Web Usability: The Practice of Simplicity (published in 22 languages), the foundational Usability Engineering (28,197 citations in Google Scholar), and the pioneering Hypertext and Hypermedia (published two years before the Web launched).

Dr. Nielsen holds 79 United States patents, mainly on making the Internet easier to use. He received the Lifetime Achievement Award for Human–Computer Interaction Practice from ACM SIGCHI and was named a “Titan of Human Factors” by the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society.

· Subscribe to Jakob’s newsletter to get the full text of new articles emailed to you as soon as they are published.

· Read: article about Jakob Nielsen’s career in UX

· Watch: Jakob Nielsen’s first 41 years in UX (8 min. video)

Love the forward thinking of this! I think there's a middle ground; rather than a future where everyone is only interacting with an ai agent, the "manual" aspect of interaction will still continue. We're visual creatures and interacting purely through language is slow and imprecise (this is coming from someone who's been designing convo ai for nearly a decade). There's likely to be a world, or at least a phase, where there's a new level of meta data that enables better AI traversal and usage underneath the existing human interaction layers we're already used to. Calling out CUA is a great example; it's a band-aid technology because structured meta data doesn't exist for the ai agent to use. When meta data does exists (e.g., HTML), it's so inconsistently structured it's essentially unusable. Overall, totally agree that we're quickly moving into an agentic ai world and there are going to be huge implications for UX and every profession. It's probably going to be a little less one-tech-to-rule-them-all and a little more messy.

Interesting post Jacob. In the early days of the internet, there were concerns that libraries might become obsolete, but this has not happened. Since the 1990s, the use of public libraries in the United States has generally increased, despite the rise of the internet. Public libraries have adapted to the digital age, providing access to computers, the internet, e-books, and other digital resources. They have also expanded their role as community hubs offering programs, workshops, and educational services beyond traditional book lending.

Is there is similar path for UI UX development? IMHO I believe there are opportunities that will present themselves, unknown paths to richer experiences for the user that supersede (or leverage) the role agents provide.