Does AI Numb the Brain?

Summary: Will AI turn our brains to mush? History suggests otherwise. From writing to calculators to spell check, new tech has always sparked fears of cognitive decline. But AI, like previous innovations, will free our minds for deeper thinking. Embrace AI as a forklift for the mind. AI won't make us stupid — it’ll make us smarter.

AI is taking over many cognitive burdens from humans. This is why I say that “AI is a forklift for the mind.” It handles many of the tedious details that humans previously needed to do. Countless studies have found that AI narrows the skill gaps between the high and low performers: it helps everybody, but it uplifts the weaker staff more than it does the top staff.

I have read much speculation about the possible negative effects of allowing AI to take over much of our brain work. If we don’t exercise our brains, they’ll turn to mush.

My slogan of AI as a forklift for the mind provides a handy comparison: in the past, warehouse workers needed to be strong because they carried heavy boxes around all day. Now, the forklift trucks do the lifting. This has two benefits:

Huge productivity boosts (like we’re also seeing from AI) because the forklift can carry substantially more weight than even the strongest worker and because it can move the pallets at a faster pace and lift them to higher locations on the pallet racks.

Narrowing the strength gap allows less musclebound staff to be employed as forklift drivers and make a good living.

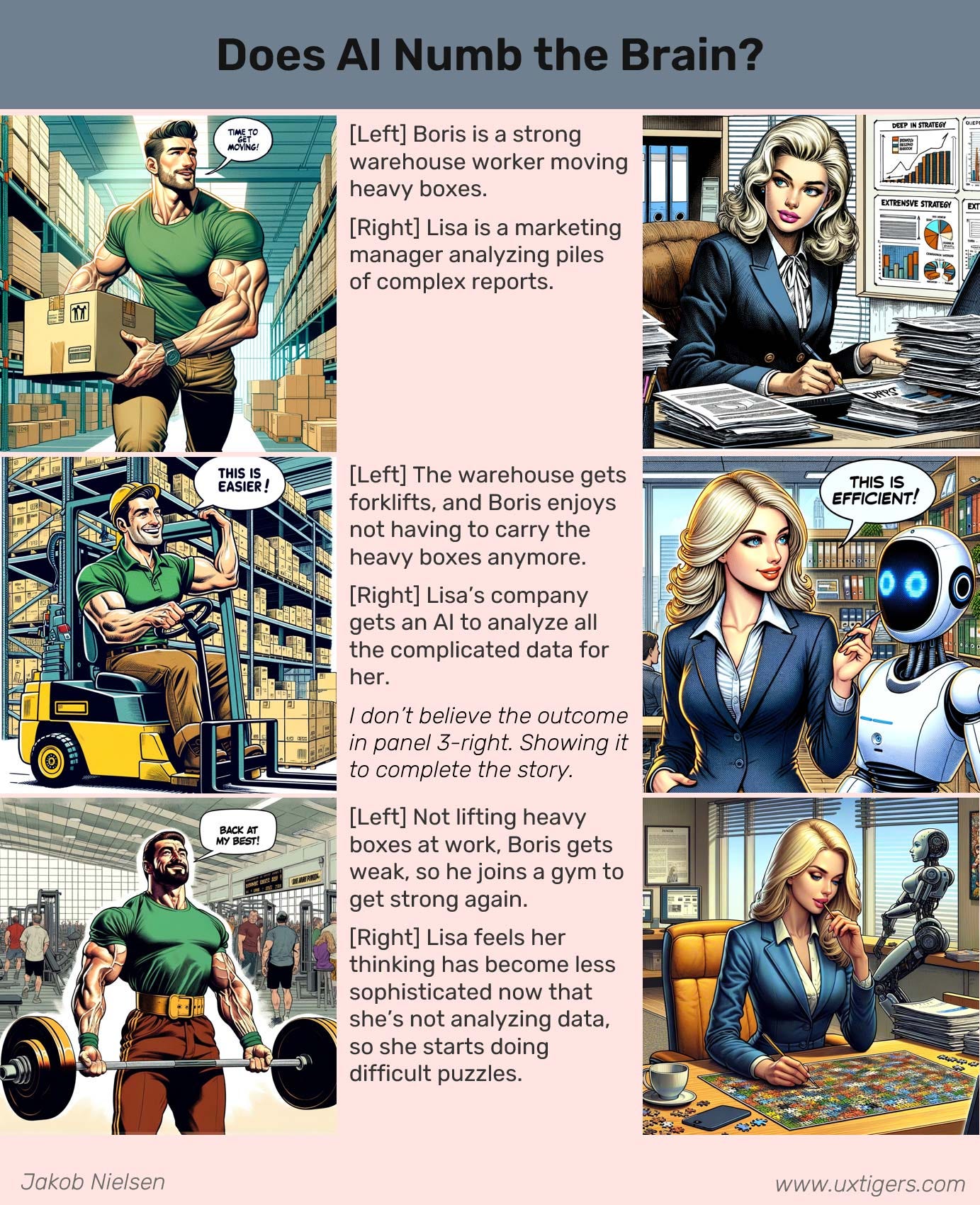

However, as shown in the following infographic, now that warehouser workers sit in a driver’s seat all day and don’t lift heavy boxes, their formerly bulky muscles will shrink, and the workers will no longer be superbly fit as a side effect of their jobs. A warehouse worker who wants to be strong will have to join a gym and work out.

Left column of panels: Automating manual labor saps workers’ muscles and requires them to work out to stay strong. Right column of panels: will automating cognitive labor similarly weaken knowledge workers’ brains? (Story Illustrator GPT) Feel free to copy or reuse this infographic, provided you give this URL as the source.

Historical Precedents for Technology Weakening the Mind

The open question is whether AI will lead to the result shown in the bottom-right panel of my infographic: weakening users’ minds, possibly requiring them to turn to puzzles to stay sharp.

Let’s look at some historical precedents.

370 BC: Writing Undermines Memory and Dialectic Understanding

In Plato’s “Phaedrus,” Socrates voiced significant concerns about the impact of writing on memory and understanding. He argued that writing leads to forgetfulness because individuals would rely on external symbols rather than internal memory. Socrates believed that true knowledge comes from active, spoken discourse rather than passive written texts, which cannot engage in dialogue or adapt to the reader's needs.

Socrates illustrated his point through the myth of the Egyptian gods Theuth and Thamus, where Theuth, the inventor of writing, claims it will improve wisdom and memory. Thamus, however, counters that it will instead cause forgetfulness and give only the appearance of wisdom, as people will read without truly understanding.

Socrates also compared written words to paintings that seem alive but cannot respond to questions. He emphasized the importance of dialectic, the art of dialogue, for achieving true knowledge, suggesting that knowledge conveyed through writing lacks the dynamism and adaptability of spoken discourse.

Do you think Socrates was right or wrong? He was surely right in deploring the effect of writing on memory: ancient techniques like the memory palace have been lost and nobody bothers memorizing long poems like the Iliad. The concept of authorship changed dramatically with the introduction of writing and is changing again with AI.

On the other hand, present-day humans can master vastly more information, exactly because we don’t have to memorize it. And while it’s true that any one document is “dead” in the sense that it can’t be queried, we can access varied perspectives by reading multiple documents.

The “memory palace” was a mnemonic aid used by most ancient speakers: you would envision a grand palace with each room holding a key point in the speech. By virtually “walking” through the palace rooms in a predetermined sequence, the speaker would be reminded of his or her next point at the appropriate time. (Ideogram)

My conclusion is that Socrates was broadly wrong, even as he got some specifics right. On balance, writing has been a boon for humanity and for intellectualism.

1973: Pocket Calculators Undermine Students’ Arithmetic Skills

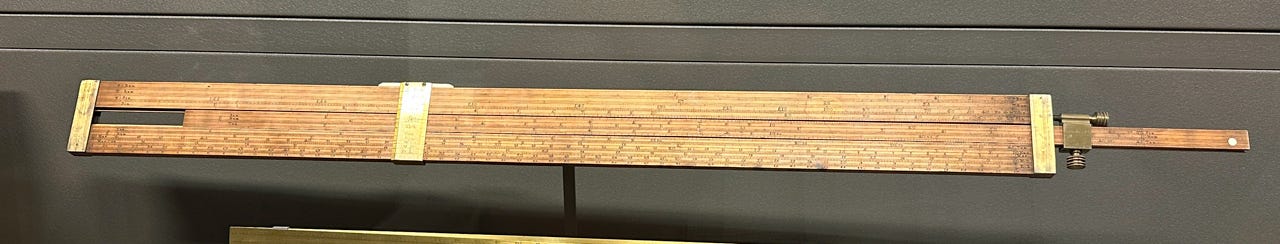

When I started high school, many naysayers deplored electronic calculators and wanted to ban them from schools. My parents gave me an advanced calculator anyway. It cost a fortune. And we were still taught how to use a slide rule and were expected to buy and use slide rules in the science classes. What a waste of time — I never used a slide rule after graduation, though I was reminded of them during a recent visit to the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.

This is a fancier slide rule than the one I used in high school. Real photo by Jakob Nielsen from the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris, March 2024.

Did the introduction of calculators undermine students’ arithmetic skills? Absolutely. Most kids these days can’t do math in their heads. Even very simple calculations will stump the majority of the population if they aren’t allowed to use a calculator. (Or the equivalent in the form of a spreadsheet or other software.) Quick, what’s 374+237?

It’s bad that many people have lost the ability to roughly understand even the relative magnitudes of numbers. But what does it matter that they can’t perform accurate calculations without calculators or computers, since these tools are always at hand?

1995: Spell Checking Undermines Writers’ Spelling Abilities

Last example: when spell checks became common on personal computers in the mid-1980s, many lamented the assured drop in writers’ spelling abilities. These laments grew stronger when spell checks started to run as a background process in 1995, meaning that the user didn’t even have to activate a spell check feature to be scolded by a squiggly line under any misspelled word. Autocorrect is even worse.

Autocorrect has led many a writer astray by “fixing” a typo the wrong way. AI will come to the rescue shortly, by allowing spell checks that take the meaning of a sentence or paragraph into account when checking words.

It’s also surely correct that many people are poorer spellers now that this burden can be offloaded to computers. But overall spelling accuracy has improved for the documents readers are consuming, which is a more important metric.

Will AI Require Mental Exercise?

These — and many more — historical examples show that offloading human cognitive burdens to technology is often accompanied by predictions of doom as people lose the ability to manually perform the now less-used skills. While some loss of human skill has usually resulted from these technologies, overall human performance has blossomed, once people were able to devote their brain power to more fruitful uses than, for example, trying to memorize a memory palace instead of relying on speaker notes.

Today’s doomers will no doubt retort that AI is different. I always react with instinctive skepticism to anybody claiming that “this time it’s different.” Usually, it isn’t.

AI is indeed different in that it can do more, but it’s still ultimately a tool.

Proper use of AI treats it as such and results in human-AI symbiosis, where both parties contribute their intelligence. This is why I don’t believe in the outcome in my infographic at the beginning of this article. Yes, if warehouse workers don’t lift heavy boxes, their muscles will weaken. But if knowledge workers have cognitive tasks performed by AI, that doesn’t mean that their brains will weaken and that they must turn to solving puzzles.

On the contrary, as AI takes over the mundane and repetitive tasks, it leaves humans to exercise our brains with more rewarding — but also more challenging — tasks. AI doesn’t remove the need for human thinking, but it does require us to think deeper thoughts.

About the Author

Jakob Nielsen, Ph.D., is a usability pioneer with 41 years experience in UX and the Founder of UX Tigers. He founded the discount usability movement for fast and cheap iterative design, including heuristic evaluation and the 10 usability heuristics. He formulated the eponymous Jakob’s Law of the Internet User Experience. Named “the king of usability” by Internet Magazine, “the guru of Web page usability” by The New York Times, and “the next best thing to a true time machine” by USA Today. Previously, Dr. Nielsen was a Sun Microsystems Distinguished Engineer and a Member of Research Staff at Bell Communications Research, the branch of Bell Labs owned by the Regional Bell Operating Companies. He is the author of 8 books, including the best-selling Designing Web Usability: The Practice of Simplicity (published in 22 languages), the foundational Usability Engineering (26,789 citations in Google Scholar), and the pioneering Hypertext and Hypermedia (published two years before the Web launched). Dr. Nielsen holds 79 United States patents, mainly on making the Internet easier to use. He received the Lifetime Achievement Award for Human–Computer Interaction Practice from ACM SIGCHI and was named a “Titan of Human Factors” by the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society.

· Subscribe to Jakob’s newsletter to get the full text of new articles emailed to you as soon as they are published.

· Read: article about Jakob Nielsen’s career in UX

· Watch: Jakob Nielsen’s 41 years in UX (8 min. video)

I use AI as a brainstorming partner. And since I write lots of content, one way I try to 'keep fit' is coming up with the idea rather than telling the AI to do so. I don't do this often, but occasionally when I do, my ideas tend to be better and fresher.

Deep thinking is expensive in biological terms. Our brain does all sort of tricks and shortcuts so we avoid slow thinking as much as possible (refer to is Kahneman's book Thinking, fast and slow). If our chances of prospering in an AI mediated world depend on all of us thinking more intensely, I have to say I feel pessimistic about the chances of most individuals.