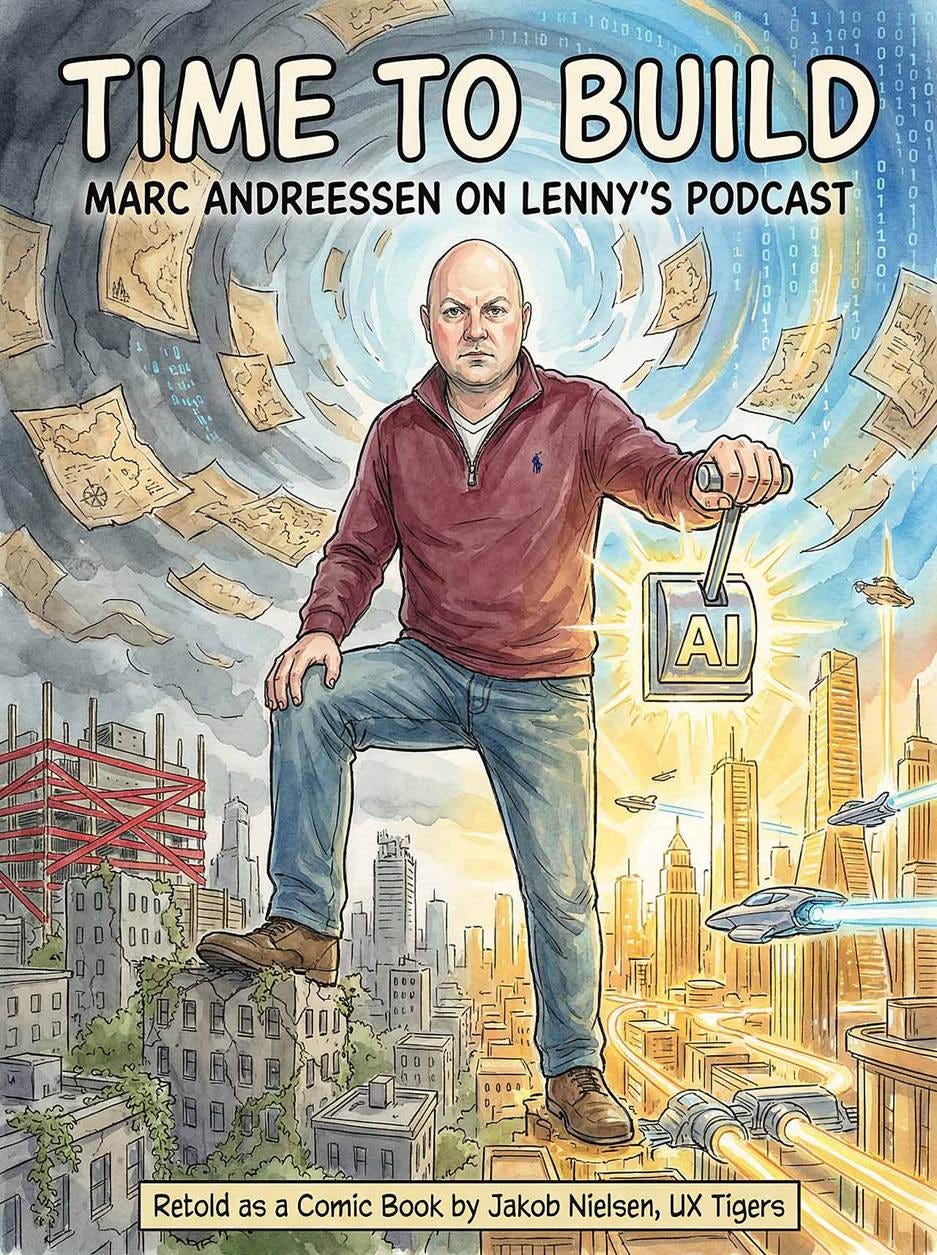

Time to Build: Marc Andreessen on a World in Transition

Summary: We possess the philosopher’s stone in the form of AI (transmuting cheap sand into expensive thought), tutoring that used to be limited to emperors (also AI), and tools that transcend biological limits (AI again). The only thing holding us back is our willingness to act, because humans still need agency. AI works. The question is: will you?

I have long been a fan of Marc Andreessen, the man who built the first practical GUI web browser and now co-leads Silicon Valley’s leading VC firm, A16Z. (See, for example, the comic strip I made about him virtually debating Jensen Huang of NVIDIA on AI trends.)

Andreessen is definitely one of the biggest heroes of the technology world, but I am starting to think that he might consider him to be the number-one biggest hero of the current decade, in tech or any other field. Every time I see a new interview with him, I feel that he’s more right and penetrating than anybody else.

This guy is not shy — and why should he be, since he most likely has genius-level IQ and has been right more often than not in the past. Andreessen frequently records new podcasts for his own firm and guests on other shows. The best I have seen him for many months is the January 29, 2026, episode of Lenny’s Podcast (YouTube, 104 minutes).

It is interesting that Andreessen was better on Lenny than in his own firm’s productions. This is much to the credit of Lenny Rachitsky’s interviewing skills. There’s a reason Lenny’s Podcast has 533K subscribers on YouTube and many more on other podcasting platforms. Lenny is very unassuming when you watch his show: it’s about the guest, not about Lenny, and that’s why he is great.

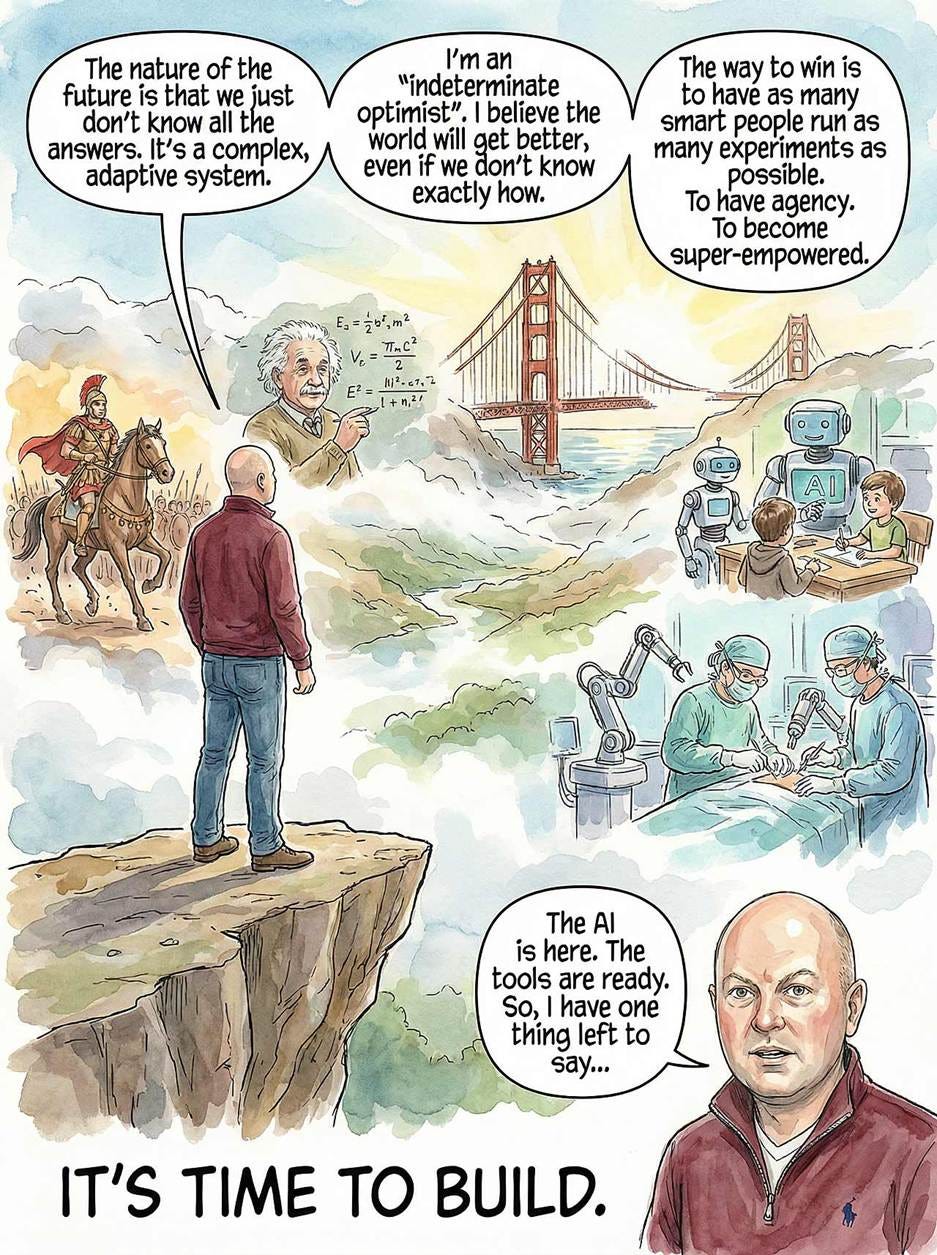

I decided to make the following comic strip about the most interesting things Marc Andreessen said on Lenny’s Podcast, but I encourage you to watch the entire episode, even though it runs almost two hours. Well worth the time.

Remember that the comic strip character “Marc” is my creation and that what “Marc” says in my strip is not identically the same as what the human Marc Andreessen said in the podcast. Differences are either my artistic license in condensing 104 minutes of video into 12 pages of comics, or they are my fault.

I made all the illustrations in this article with Nano Banana Pro and had to generate many more variations than I’m showing here to get a decent level of character consistency, even though the strip only features a single character.

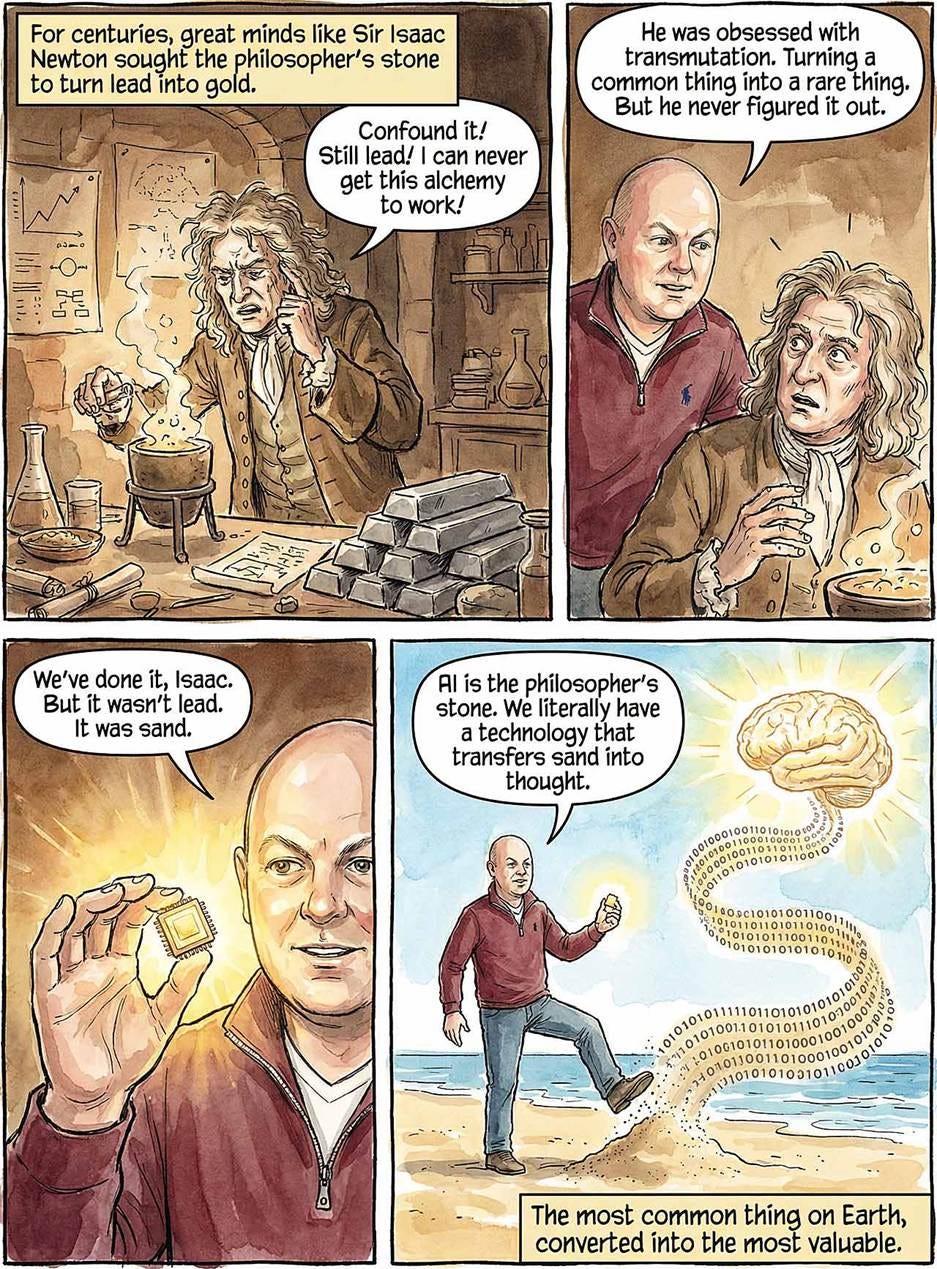

Marc draws a fascinating parallel between AI and the ancient alchemists’ quest for the philosopher’s stone. Scientists like Sir Isaac Newton spent decades obsessed with transmuting lead into gold: converting something common into something rare and valuable. They never succeeded. AI, Marc argues, has actually achieved something even more remarkable: it transforms sand (silicon, the most common element on earth) into thought (the rarest and most valuable thing). This framing positions AI not as incremental technological progress but as the realization of an age-old dream, making it “the philosopher’s stone” that alchemists could never discover. Marc emphasizes this to his 10-year-old son, teaching him that mastering AI is like learning to wield this magical tool that converts the mundane into the extraordinary.

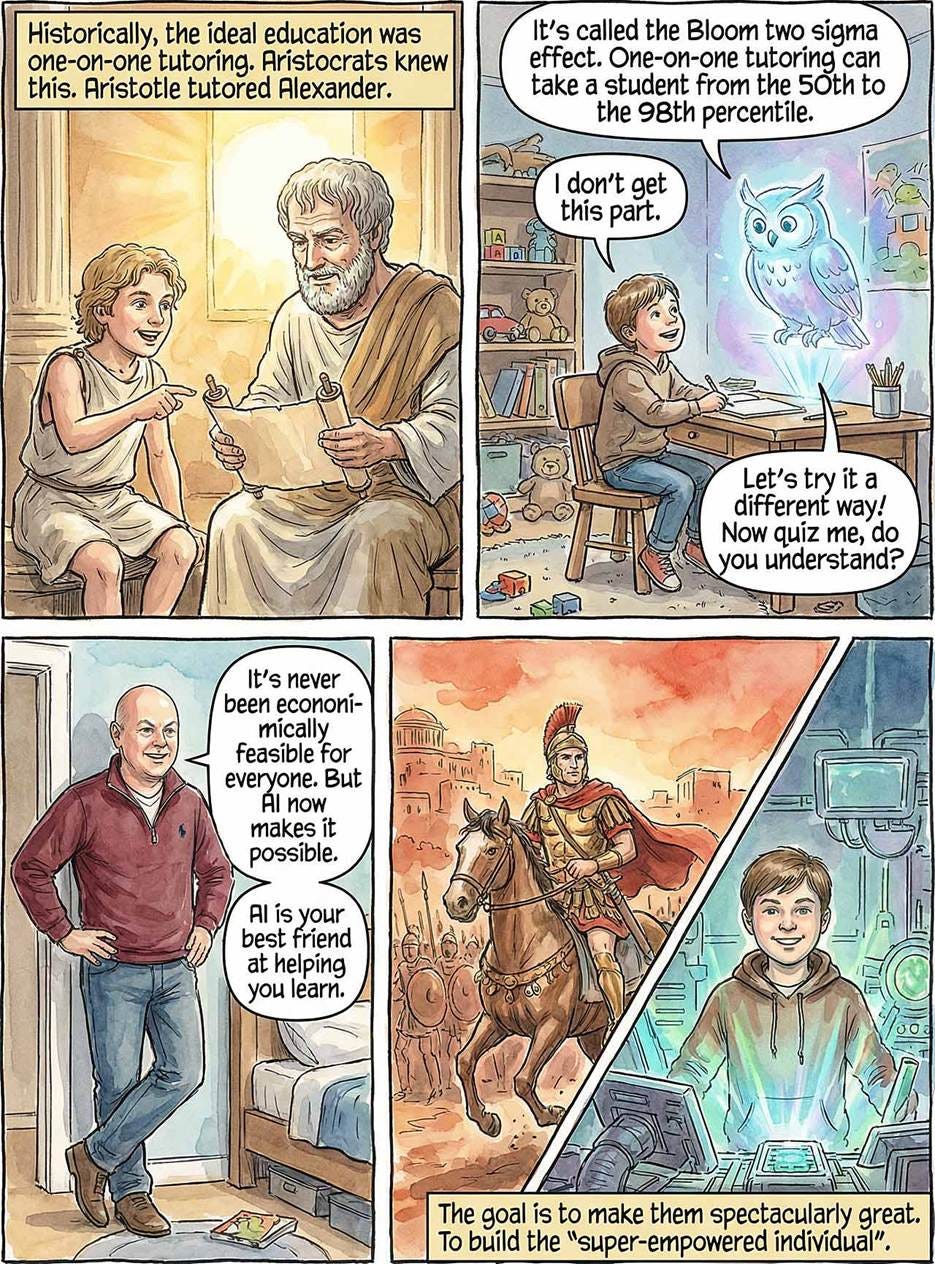

Bloom’s “two sigma effect” is a well-documented finding that one-on-one tutoring routinely raises student outcomes by two standard deviations, taking a child from the 50th percentile to the 98th percentile. Marc notes this has been known for centuries, with every royal family and aristocratic class understanding it, citing Alexander the Great being tutored by Aristotle as the prime example of how personalized education produces world-changers. The problem, Marc explains, is that one-on-one tutoring has never been economically feasible for anyone except the wealthiest families. AI fundamentally changes this equation: now any child can ask an LLM infinite questions, receive instantaneous feedback, request explanations at different comprehension levels, and even be quizzed on their understanding. This democratization of elite education represents one of AI’s most profound social contributions.

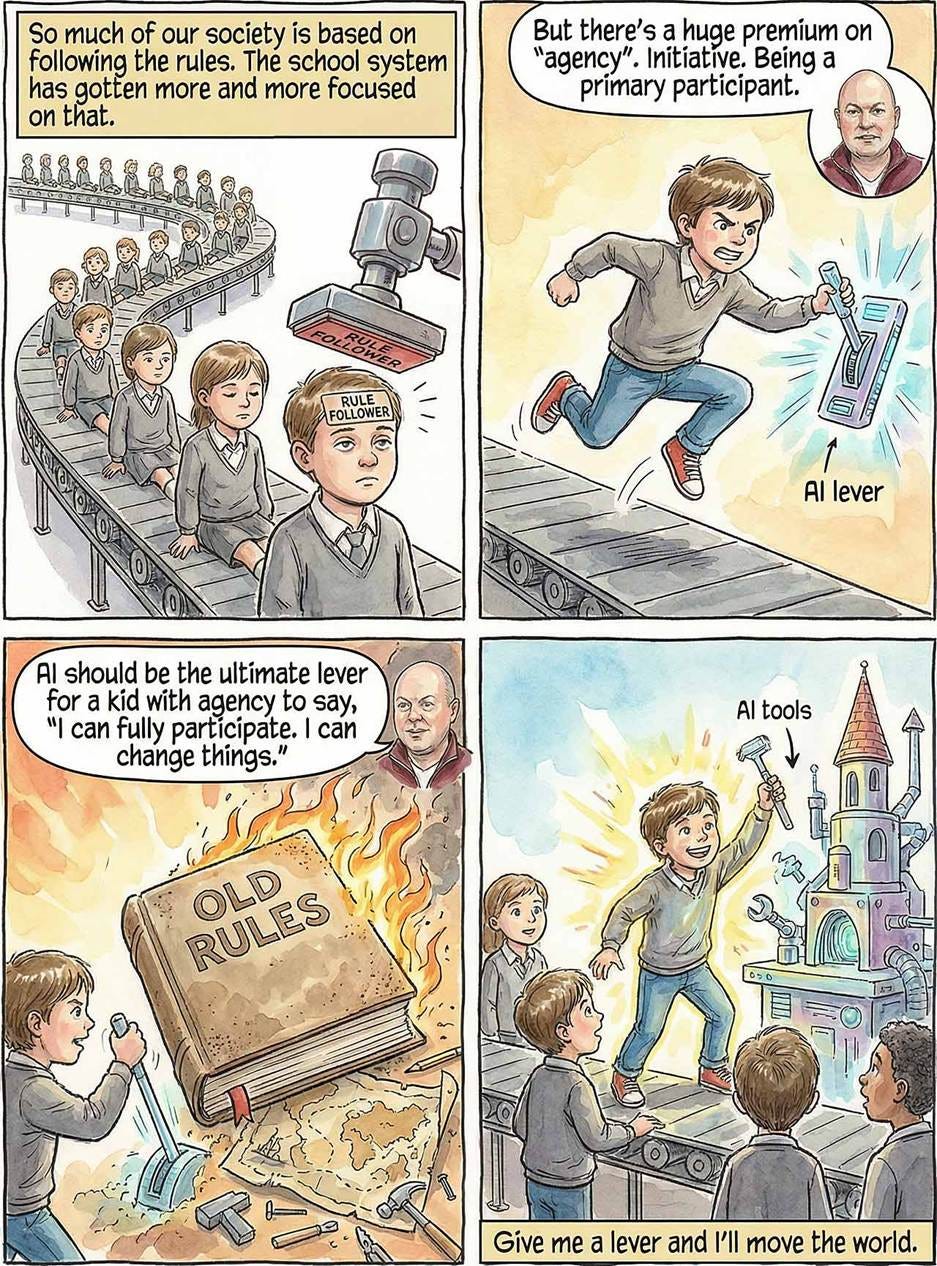

Marc discusses the increasingly popular concept of agency, which he initially found puzzling but now recognizes as crucial. The term describes initiative, the willingness to just do things, being a “live player” who participates in events rather than passively observing. Marc observes that society, particularly the education system, has increasingly focused on training kids to follow rules, creating people whose default assumption is compliance. While acknowledging some structure matters, Marc emphasizes that huge premiums in life go to those who can take full responsibility, lead projects, and create something new. AI becomes the ultimate enabler for kids with agency, allowing them to be primary contributors in everything from physics to art to coding.

(See my article Future-Proofing Education.)

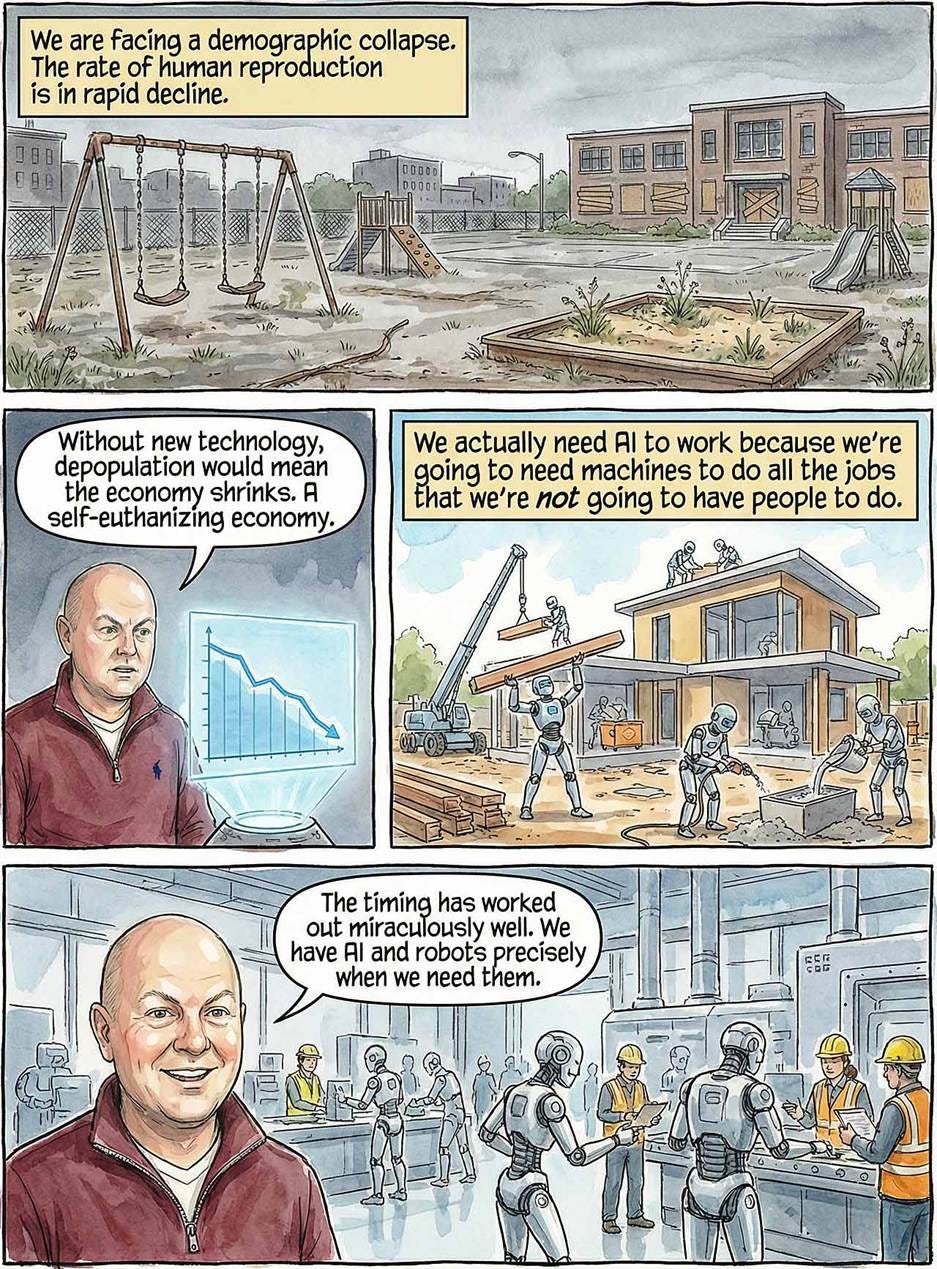

The world faces demographic collapse, with birth rates below replacement level in numerous countries, including the US and China. Many nations will depopulate over the next century. Without AI, Marc argues, we would be staring at economic catastrophe: shrinking economies, diminishing opportunity, and a self-euthanizing civilization. The timing of AI’s emergence is therefore miraculously well-suited to humanity’s needs: we need AI and robots precisely when we’re running out of workers to sustain economic growth. Rather than viewing AI as a job-destroyer, Marc reframes it as the essential technology that will perform the work that declining human populations cannot, preventing economic stagnation and enabling continued prosperity.

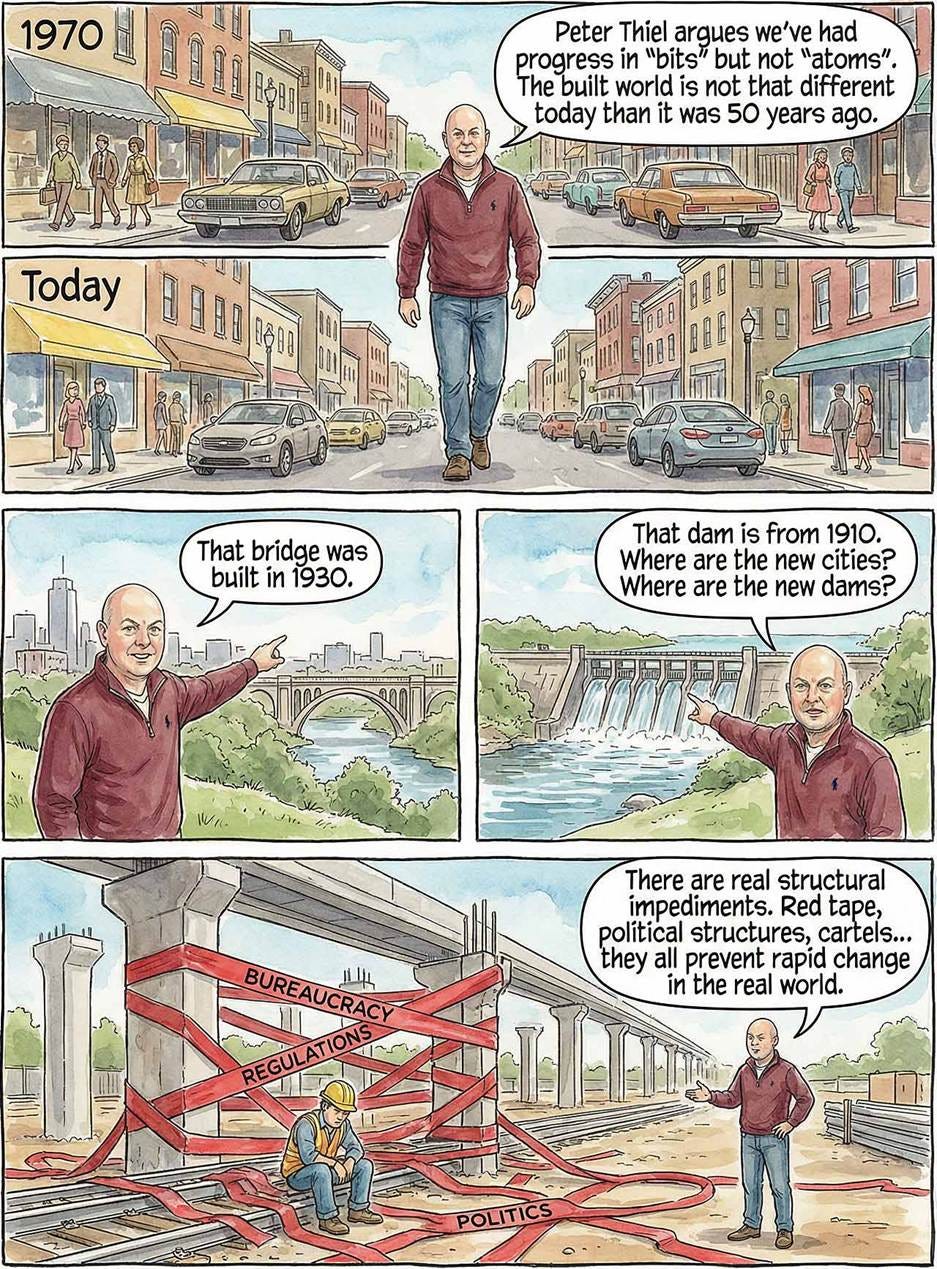

Marc acknowledges that Peter Thiel’s critique of technological progress (that we’ve had progress in “bits” but not “atoms”) is more correct than Marc initially gave him credit for. While the last 50 years feel like a time of great change, productivity growth statistics tell a different story: technological impact on the economy has been running at half the pace of 1940–1970 and a third the pace of 1870–1940. The physical world provides stark evidence: we still use bridges from the 1930s, dams from 1910, buildings from 1960, and cities founded in 1880. Marc asks pointedly: Where are the new cities, new dams, where’s the California high-speed rail? This stagnation stems from bureaucratic red tape, regulations, unions, cartels, and political structures that actively prevent change. These same forces will likely slow AI’s real-world impact, making utopian or dystopian predictions of overnight transformation unrealistic.

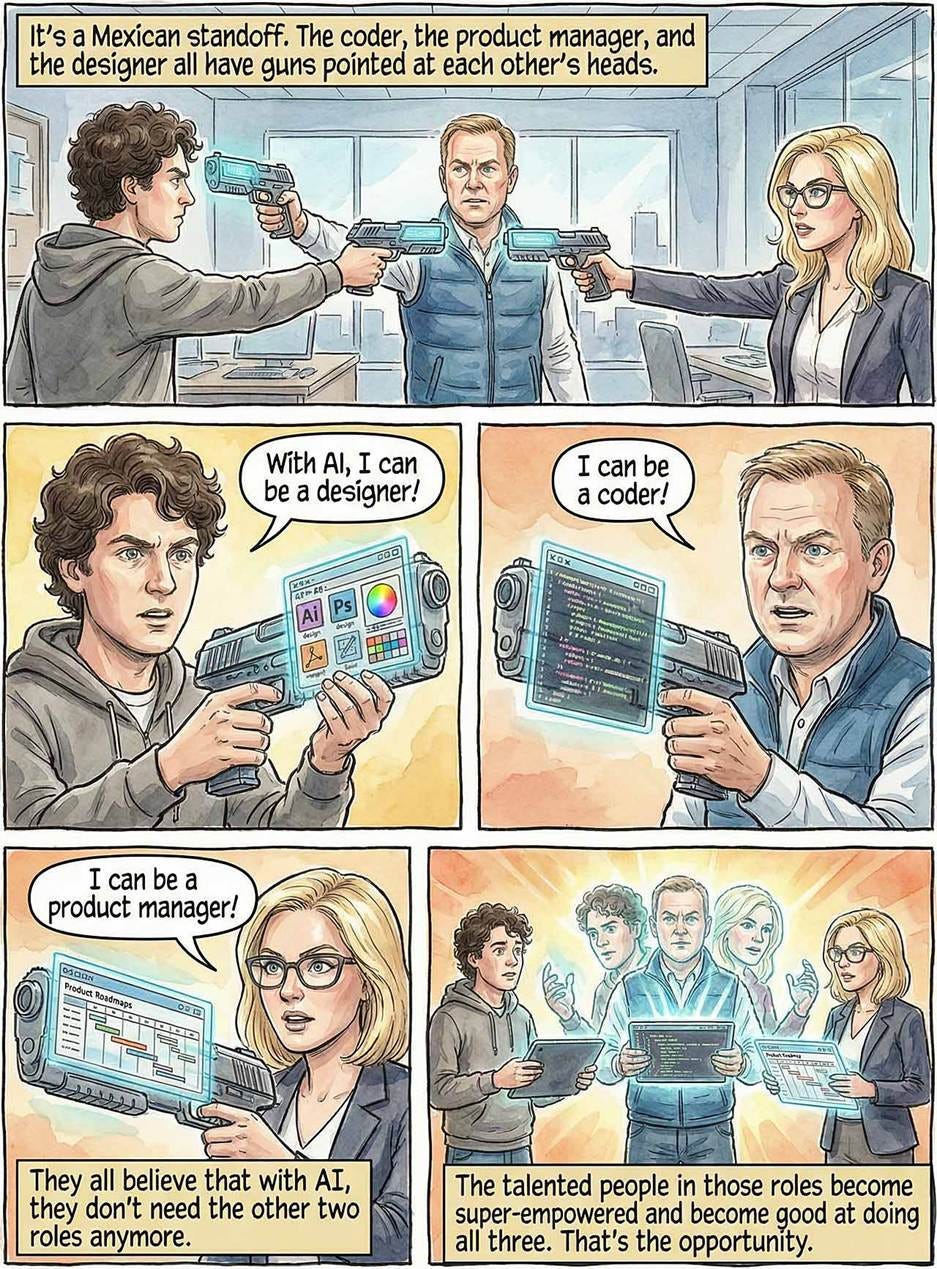

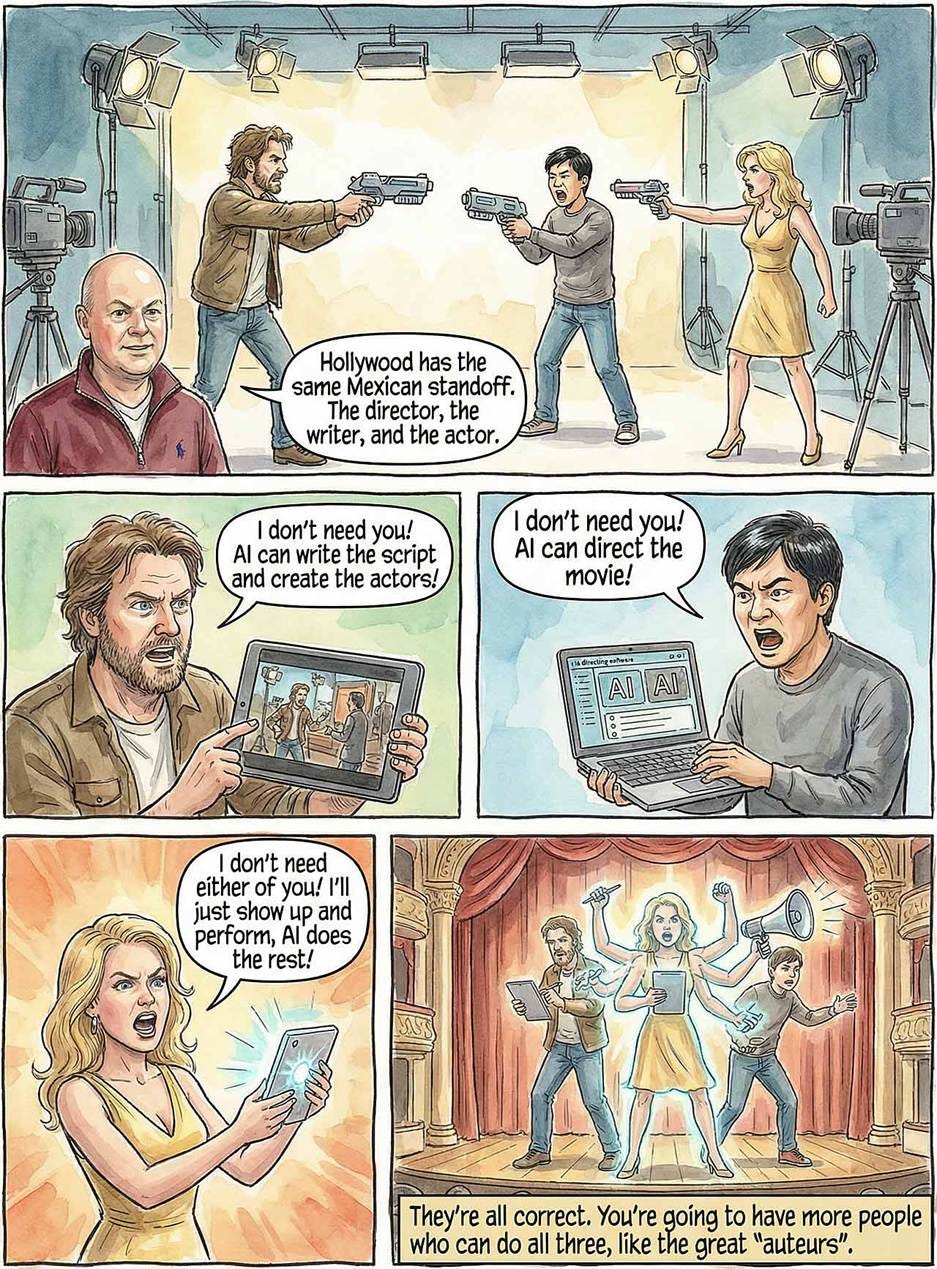

Marc describes a “Mexican standoff” among product managers, designers, and engineers: three roles that have traditionally operated in separate silos. Now, every coder believes they can also be a product manager and designer because they have AI; every product manager thinks they can code and design; every designer knows they can do the other two roles. The fascinating part, Marc notes, is that they’re all essentially correct since AI really is good at all three functions. The traditional stovepipe career paths may disappear, replaced by superpowered individuals who combine capabilities across all three domains. Rather than viewing this as threatening, Marc sees enormous opportunity: talented people in any of these roles can expand laterally, becoming extraordinarily valuable because they can build and design products from scratch, which is the most valuable capability of all.

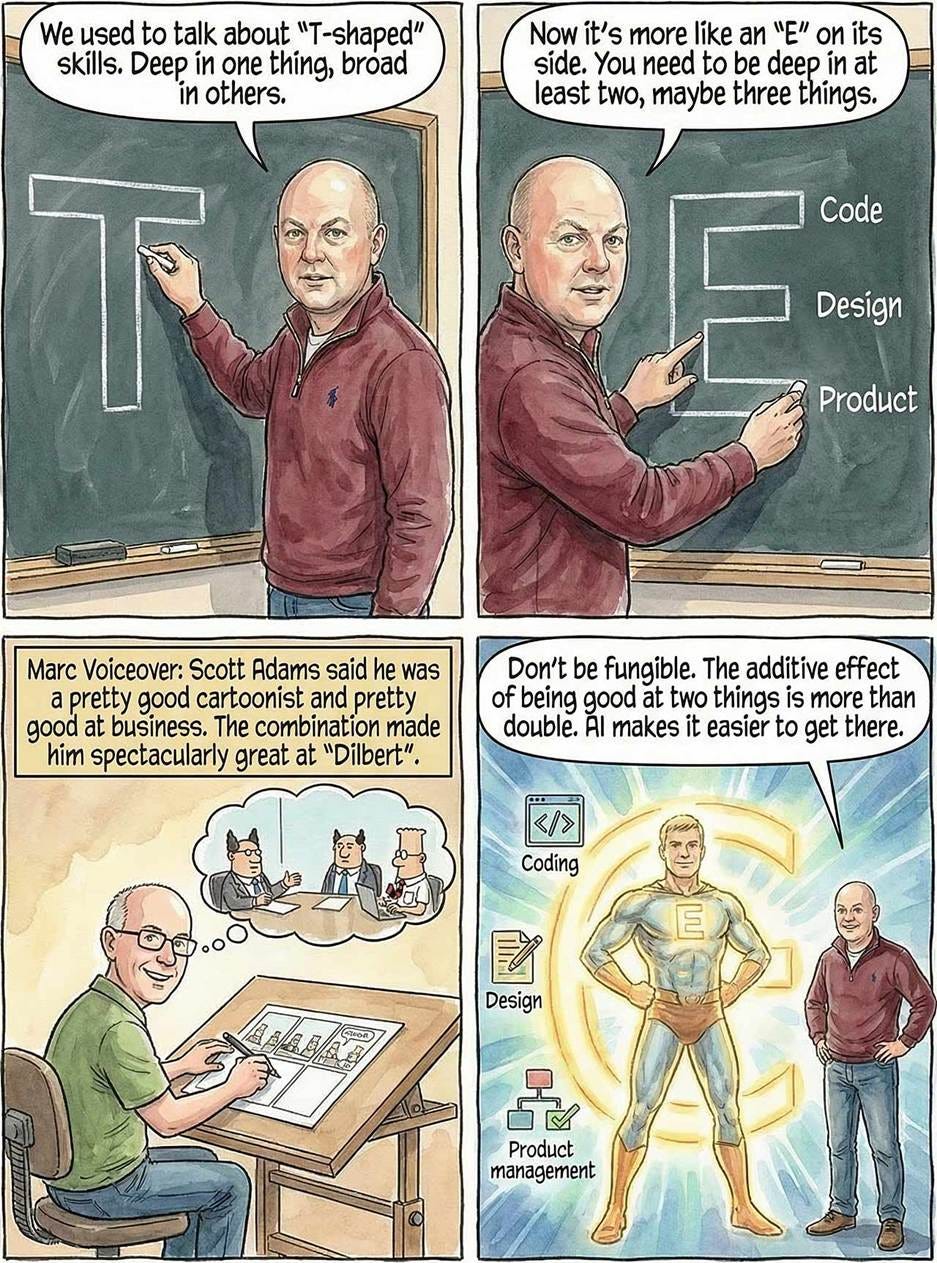

We are changing from a “T-shaped” to an “E-shaped” approach to career development, referencing the late Scott Adams’ career advice that being good at two things creates more than double the value, and three things more than triple. Adams couldn’t have created Dilbert as just a cartoonist or just a business person: the combination made him spectacularly great in a unique niche. Marc’s friend Larry Summers frames this as “don’t be fungible”: if you’re just one thing, you can be replaced, but rare combinations make you invaluable. In the AI era, the breadth of the “T” represents how many domains you can use AI tools to perform well in, while the depth represents your deep expertise in at least one area. Someone deep in coding who can use AI for design and product management becomes a “triple threat.” capable of feats previous generations couldn’t imagine.

Marc extends his Mexican standoff analogy to Hollywood, where directors, writers, and actors are experiencing the same triangular tension. Directors now think they don’t need writers (AI can write scripts) or actors (AI can generate performances); writers believe they don’t need directors (AI can direct) or actors; actors think they can have AI handle writing and directing while they simply perform. Each participant in this triangle believes they can eliminate the other two roles. Marc suggests this disruption may actually benefit creative talent: more people will be able to combine writing, directing, and acting capabilities; the combinations that historically produced the greatest “auteurs.” Hollywood calls these multi-talented creators who can write and direct (or write and act, or do all three) the true creative forces that move the industry forward.

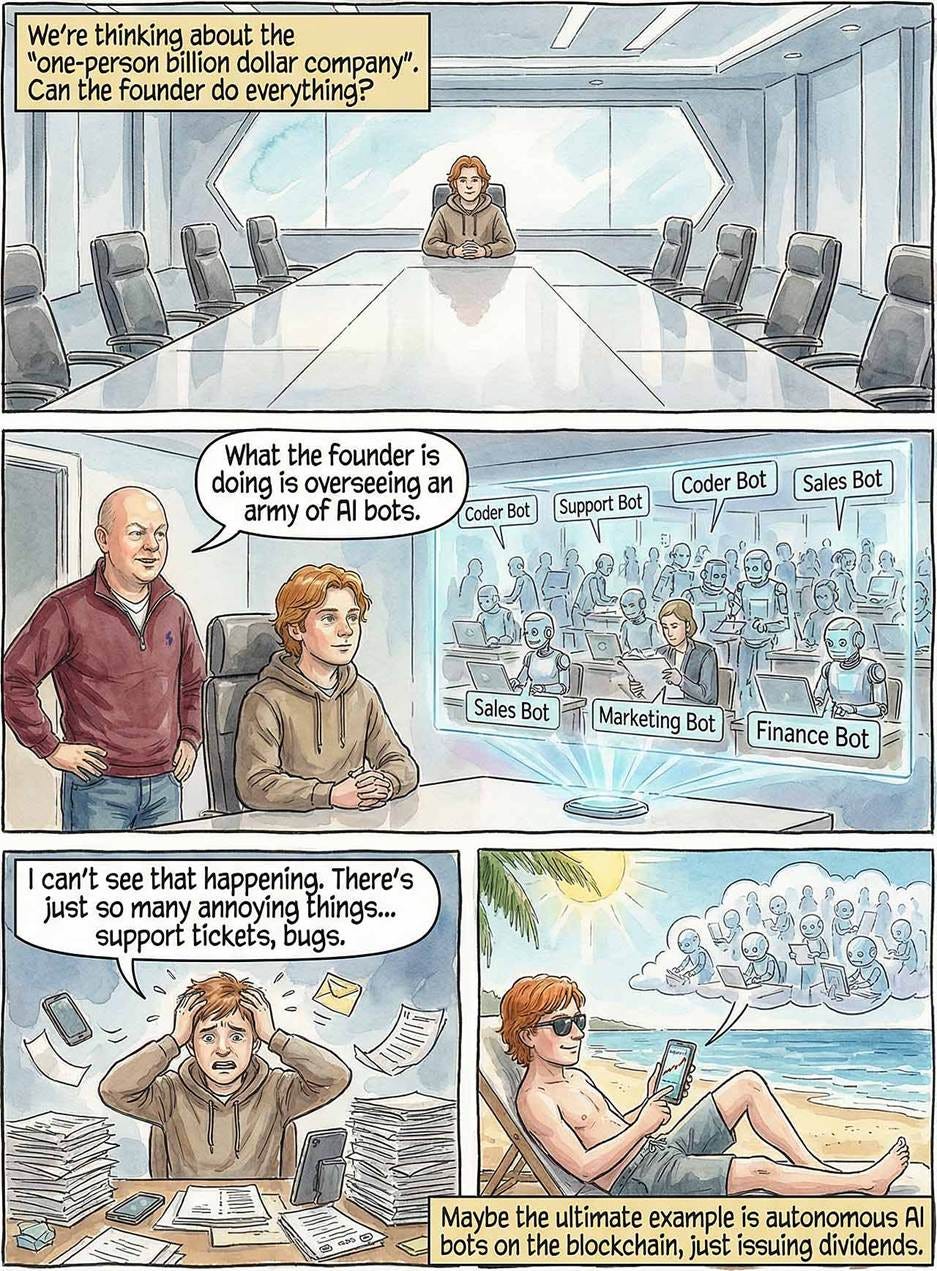

Marc identifies the “one-person billion dollar company” as a kind of holy grail in Silicon Valley, with Bitcoin (Satoshi Nakamoto) being the most spectacular example, followed by Ethereum and exits like Instagram and WhatsApp, all built by tiny teams. Most software companies still end up with large headcounts, but Marc notes that leading-edge founders are questioning whether AI fundamentally changes the definition of what a company requires. He speculates about whether founders can build entire companies by overseeing an army of AI bots, or even whether autonomous AI agents on blockchains could function as businesses issuing dividends with no human involvement at all. While acknowledging the open question of whether contractors count and the inevitable “annoying edge cases” that still require human attention, Marc confirms this represents the cutting edge of founder thinking.

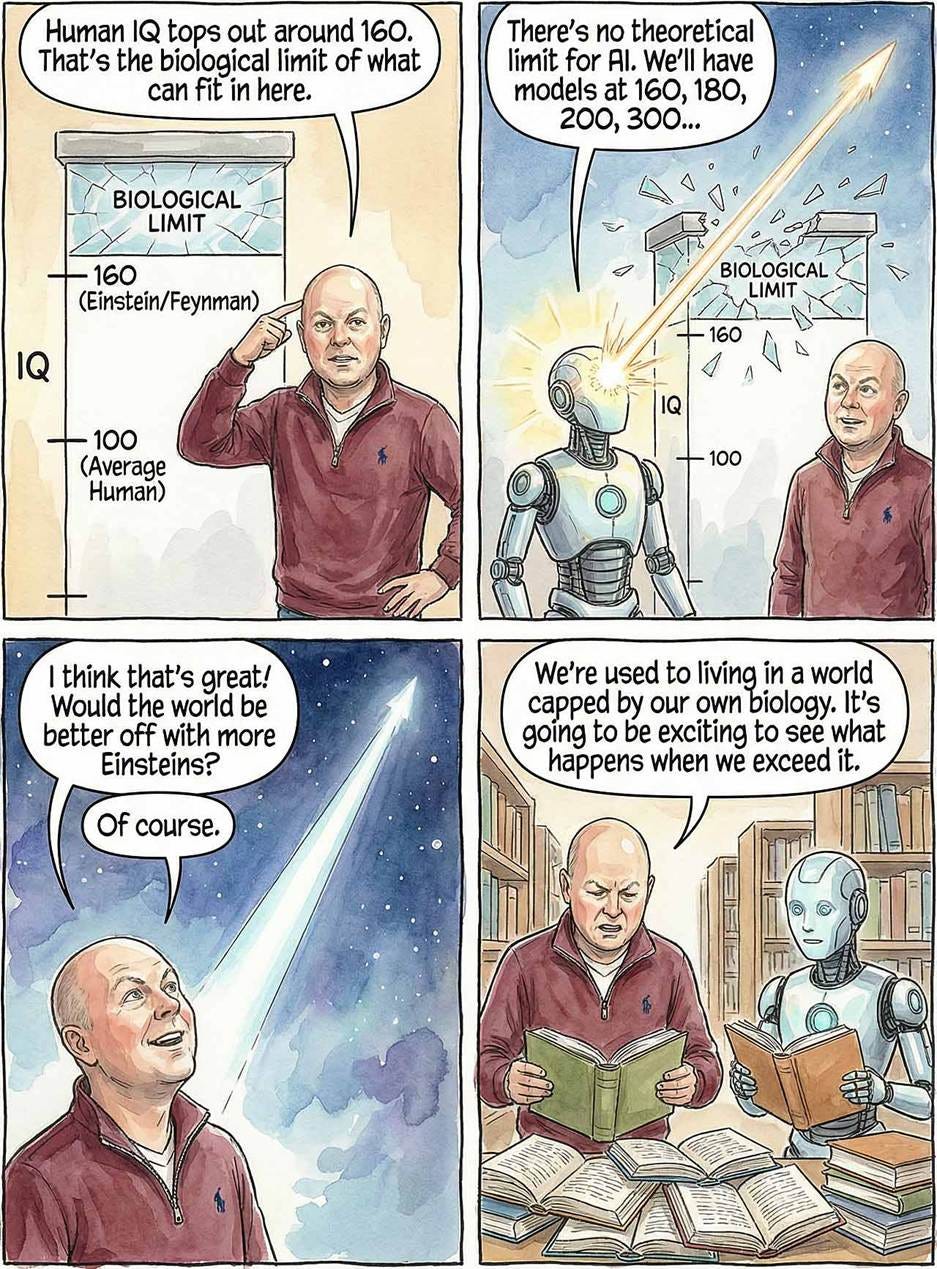

Marc challenges the common framing of AGI as “human-equivalent intelligence,” arguing it dramatically understates AI’s potential. Human IQ tops out around 160 due to biological limitations: Einstein-level intelligence that produces breakthrough physics. Current AI models test around 130–140, approaching and in some mathematical domains reaching 160-level performance. But unlike humans, AI has no biological ceiling: Marc anticipates AI will reach 160, then 180, then 200, 250, 300 and beyond. This isn’t frightening, it’s wonderful, like having access to more Einsteins. We’ve been capped by our own biology for so long we don’t understand how good “good” can get. The ability to harness 300-IQ tools for medicine, science, and engineering represents unprecedented human augmentation rather than replacement.

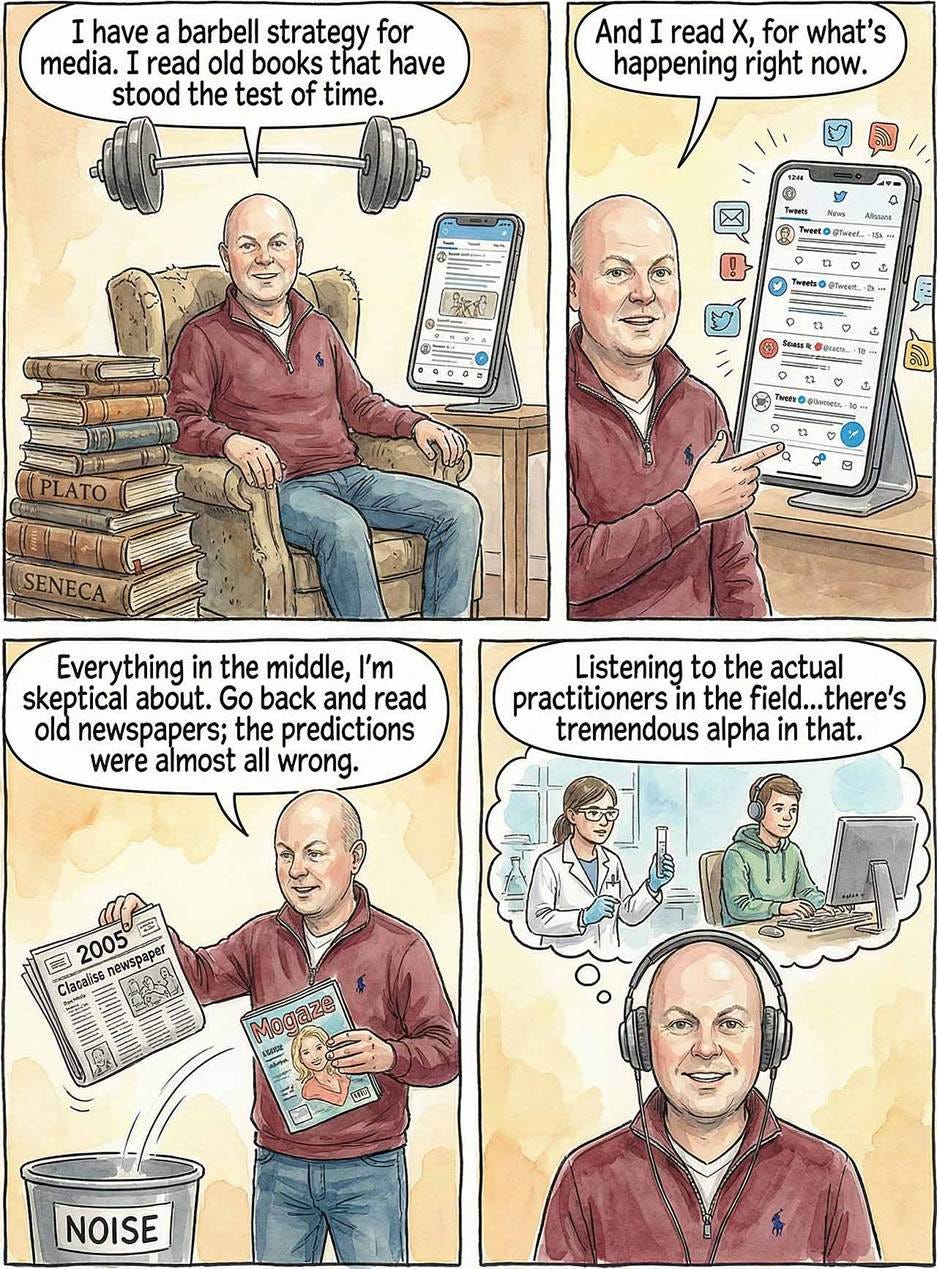

Marc describes his media consumption as a “perfect barbell strategy”: he reads X/Twitter for up-to-the-minute developments and old books (50+ years old) that have stood the test of time, while remaining deeply skeptical of everything in between. His reasoning: if you read last year’s newspaper, almost none of the predictions played out correctly, and magazines are even worse because their longer production cycles make content obsolete before publication. Instead, Marc prizes direct access to domain practitioners: founders, researchers, experts who actually do the work, through podcasts, newsletters, and Substack. He notes this represents a fundamental shift from the mass media era where everything was mediated through TV and newspaper interviews to today’s world where smart people explain themselves directly, providing “tremendous amounts of alpha” unavailable in traditional media.

The eleven points covered in my comic strip (the full video has more) converge on a single urgent conclusion: humanity stands at an inflection point where the tools for unprecedented creation are available, but capturing their value requires action, agency, and ambition. The philosopher’s stone exists: AI transforms common inputs into extraordinary outputs. Elite education is democratized through AI tutoring. The demographic crisis creates urgent demand for productivity solutions.

The historical stagnation Andreessen and Thiel identify isn’t a technological limitation but institutional sclerosis: bureaucracy, regulations, and risk aversion that prevented building. The Mexican standoffs in tech and Hollywood aren’t crises but opportunities: artificial barriers between roles are dissolving, enabling superpowered individuals who combine skills to build what siloed specialists never could. The biological ceiling on human intelligence is becoming irrelevant as AI tools amplify human capability beyond any historical precedent.

The synthesis is clear: we possess the philosopher’s stone, the tutoring of emperors, and tools that transcend biological limits, yet we’ve spent fifty years not building new cities, dams, or transformative infrastructure. The world will depopulate without intervention; institutional gatekeepers will resist change; the legacy media will tell you why things can’t be done.

But the barbell strategy that combines immediate action with timeless wisdom points toward those with agency who break default paths. The one-person billion-dollar company isn’t a fantasy; it’s the logical endpoint of exponentially-amplified individual capability. Marc’s framework isn’t abstract optimism; it’s a call to recognize that the constraints that prevented building for decades are dissolving precisely as existential challenges (demographic collapse, economic stagnation) demand solutions.

The tools are here. The need is urgent. The only remaining variable is human willingness to act. It is time to build.

About the Author

Jakob Nielsen, Ph.D., is a usability pioneer with 43 years experience in UX and the Founder of UX Tigers. He founded the discount usability movement for fast and cheap iterative design, including heuristic evaluation and the 10 usability heuristics. He formulated the eponymous Jakob’s Law of the Internet User Experience. Named “the king of usability” by Internet Magazine, “the guru of Web page usability” by The New York Times, and “the next best thing to a true time machine” by USA Today.

Previously, Dr. Nielsen was a Sun Microsystems Distinguished Engineer and a Member of Research Staff at Bell Communications Research, the branch of Bell Labs owned by the Regional Bell Operating Companies. He is the author of 8 books, including the best-selling Designing Web Usability: The Practice of Simplicity (published in 22 languages), the foundational Usability Engineering (30,020 citations in Google Scholar), and the pioneering Hypertext and Hypermedia (published two years before the Web launched).

Dr. Nielsen holds 79 United States patents, mainly on making the Internet easier to use. He received the Lifetime Achievement Award for Human–Computer Interaction Practice from ACM SIGCHI and was named a “Titan of Human Factors” by the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society.

· Subscribe to Jakob’s newsletter to get the full text of new articles emailed to you as soon as they are published.

· Read: article about Jakob Nielsen’s career in UX

· Watch: Jakob Nielsen’s first 41 years in UX (8 min. video)

Beat me to it. Andreesen is a freaking Bond villain. He’s one of the biggest threats to humanity and democracy. I was almost willing to tolerate all the AI bullshit on this Substack given your reputation, but this? I’m out.

It's always fascinating when men who know nothing about sequential art or the comics industry use AI to make comics because they are always complete failures in the formal/compositional sense as well as being badly drawn with incomplete ideas.

Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud is a good book to read before embarrassing yourself by pretending you know someone else's art form.