UX Roundup: AI-Created Podcast | Likely to Recommend? | Unproductive Metrics | Are UIs Needed? | Faster Tech Diffusion | AI Predictions | Sam Altman Essay | AI UX Job

Summary: Podcast created by AI | What people say vs. do relative to product recommendations | Metrics that incentivize the wrong behavior | Do you need a UI? | New generations of tech innovation have spread ever-faster through the economy | AI Predictions | Sam Altman on the future of AI | AI UX job

UX Roundup for September 30, 2024. (Ideogram)

AI-Created Podcast

I used Google’s new NotebookLM service to automatically make a podcast (8 min. video) based on my article “4 Metaphors for Working with AI: Intern, Coworker, Teacher, Coach”

I made this for two reasons:

To serve fans who prefer to listen, rather than read.

To experiment with NotebookLM. I find it rather impressive, how it transformed a written article into a bantering podcast. It did take it upon itself to make up some new examples that were not in my article, but overall, it did a good job.

I added the images to the video since NotebookLM currently only creates audio. It's not a big leap to expect them to add generated video avatars of the two podcast hosts at a later date.

The two bantering hosts in the podcast don’t exist. So I had Midjourney draw them.

The ability to use AI to automatically produce an entirely new media form (bantering spoken conversations between two presenters instead of an article that is decidedly based on written language) is a great example of AI remixing. The same source material can be repurposed in as many different media forms as you care to have made, including infographics.

What People Say vs. Do Relative to Product Recommendations

You’ve probably heard about the Net Promoter Score (NPS), which measures customers’ likelihood to recommend your product or service by asking them for a rating on a 0-10 scale.

There are many reasons this is a bad metric for UX, not least that it is insufficiently granular to reflect UI design changes. However, it is one of the most common metrics for measuring overall customer satisfaction, much — or often, most — of which is driven by other factors than design.

I just wrote an article saying that you should ignore what customers say and focus on what they do.

Since NPS is purely based on asking customers’ opinions, it’s important to consider whether the responses have any relation to customers’ actions. Luckily, MeasuringU recently published a review of 7 research studies comparing respondents’ NPS ratings with their subsequent recommendation behavior.

(MeasuringU is the world’s top consultancy in UX metrics. They have an 8-day UX Measurement Boot Camp starting September 10, which I strongly recommend if you want to learn quantitative research methods. This training also provides UX research certification, which I know many people value.)

The studies show that respondents classified as “promoters” (giving a score of 9 or 10) actually later recommended the product 55% of the time (averaged across the 7 studies). Better than flipping a coin, but not by much.

More importantly, respondents classified as “detractors” (giving scores between 0 and 6) only subsequently recommended the product 18% of the time.

How much can we trust if customers say on a survey that they are dissatisfied or happy with your product? There is some relation between NPS scores and the respondents’ subsequent recommendation behavior, but less than one should think. (Midjourney)

What to make of these findings? On the one hand, there is clearly something to NPS in that promotors recommended the product 3 times as often as the detractors did.

On the other hand, it’s not very impressive that people who expressed a powerful recommendation intent only followed through with an actual recommendation to another person slightly more than half the time.

It also goes against the entire NPS philosophy that almost a fifth of those users classified as “detractors” recommend the product to a new potential customer.

These facts demonstrate the importance of differentiating between what people say and what they do.

Looking at more fine-grained data than the simplistic NPS distinction between promotors and detractors, MeasuringU found that respondents who gave the very highest score (10) were slightly more likely to recommend than lower-rating respondents (60% vs. 55%). Similarly, respondents who gave very low scores (0 to 4, on that 0-10 scale) did have a slightly lower recommendation frequency than the full set of detractors (16% vs. 18%).

To conclude, it’s not a wasted effort to ask customers whether they intend to recommend your product. The higher the score they give, the more they actually recommend. This again means that if you improve your NPS score, it probably reflects a real lift in customer satisfaction. But don’t expect that what people say on your survey is what they actually do: 45% of “promoters” say they’ll recommend you but don’t.

Metrics Should Not Be Their Own Goal

Ron Kohavi (probably the world’s leading expert on website analytics) wrote a nice short article on what he dubs “watermelon metrics” (green as money on the outside, but filled with red losses on the inside). These measures sound reasonable when first proposed, but once a product team targets the metric itself (instead of the underlying goal for which the metric is an approximation) they are led astray. Design decisions that game the metric look good on the dashboard and may generate a nice bonus. But the company will lose money.

“Watermelon metrics” look nice and green on the outside, as if they’re made of dollar bills. But once you get to the inside and see the metric in action where it’s being gamed, you may find that it turns into a stream of money losses and looks red, because people end up not working toward the true underlying goal but toward the surface metric. The map is not the terrain. (Leonardo)

One of Ron’s examples is the classic doozy of measuring programmer productivity by lines of code written. You do want highly productive developers since the best programmers are about 20x as good as bad programmers. People who produce a lot of code are likely more productive than people who produce very little code in a month. On average, this may well be true.

But once programmers get a bonus for the number of lines they write, they’ll start gaming the metric. For example, split comments across multiple lines or inserting the same code multiple times in a program instead of making it into a function call.

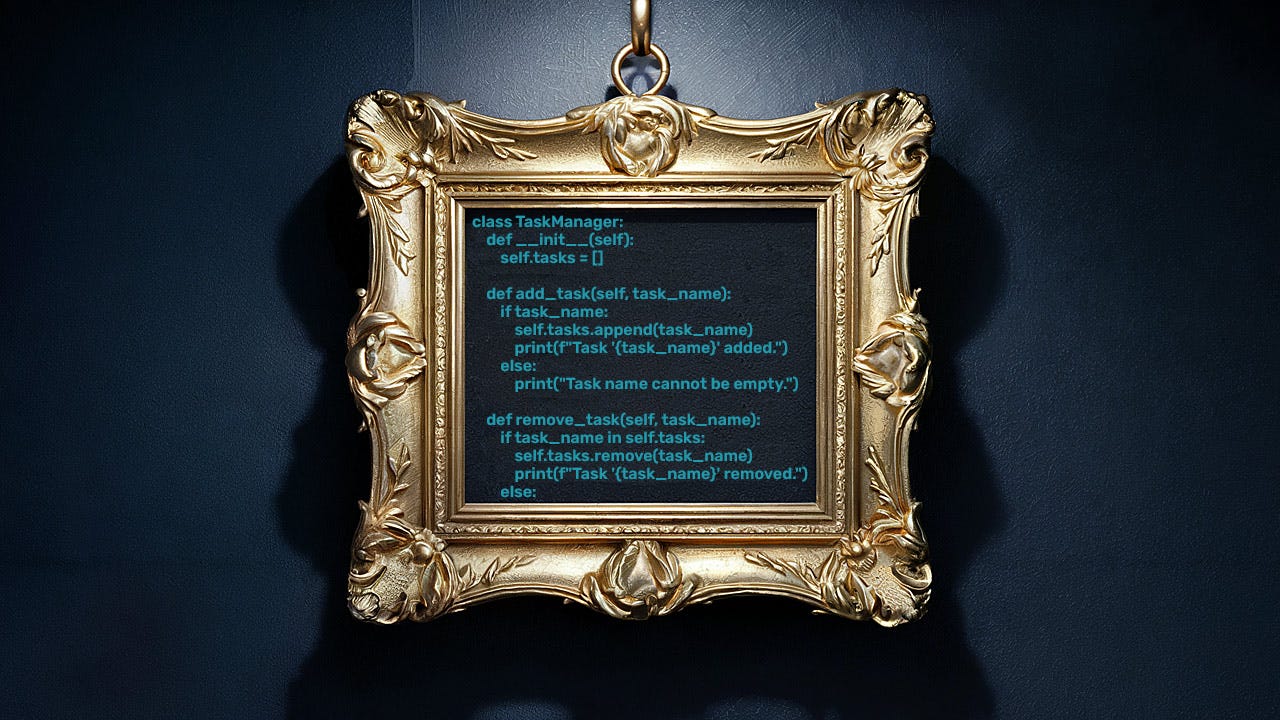

It is a “watermelon metric” to make lines of code into a trophy goal for developers instead of the more appropriate goal of producing good code that solves the problem at hand in the best manner. (Ideogram)

Do You Need a UI, or Is an API Better in the Age of AI?

The next generation of AI (about 2 years from now) will likely include a strong whiff of agents, where users empower the AI to act on their behalf. It’s possible that the subsequent AI generation (in about 4 years) will be even more agent-based.

This begs the question of whether you will need to design a user interface at all for human consumption. It’s possible that customers will no longer interact with your company by visiting your website or using your app. Instead, each customer will interact with his or her personal AI agent which has a UI fully to that person’s preference: a giggly seductive voice a la OpenAI’s “advanced voice mode”, or a serious deep voice, or anything in-between, including any visual appearance you want and the ability to instantly create visualizations that it knows you will like and understand.

The user’s AI agent will then turn around and deal with your company on behalf of its user. This means that the user will never see your carefully-designed website. Then why waste resources designing it? It may be better to allow these AI agents direct deep access to the information they need through an API.

I don’t know how antagonistic the AI-vs-AI negotiations might get. Still, this metaphorical image may represent future interactions between a customer and a company better than an image of the user browsing the company website on a computer or phone. (Midjourney)

I don’t necessarily believe in this future. I think there will likely still be some cases where users will want to engage directly with a company. If this is true, there will still be a need for a UI to support these interactions.

In fact, there was an initiative in the late 1990s called “The Semantic Web” that aimed to extend the capabilities of the existing Web by making Internet data machine-readable. Technologies like Resource Description Framework (RDF) and RDF Schema specifications tried to create a universal medium for data exchange, enabling software agents to autonomously perform sophisticated tasks for users by understanding the meaning of web content.

The Semantic Web was a miserable failure, because companies focused their effort on a human-readable presentation of their products and services, driven by the added persuasiveness of compelling visual design and good human usability. Machine-readable data was not a priority in that era.

The future might work out differently. One point is that the AI agents will have the capability to read and understand websites that are mainly designed for human consumption. This solves the chicken-and-egg problem of The Semantic Web, where users didn’t have much incentive to use its services when almost no data was available (and software vendors didn’t have any incentive to develop features for this non-existent user demand).

The open question is whether we’ll see a gradual shift from human-targeted UI design to machine-targeted API design. AI agents will prime the pump by reading UI-presented data, but companies may get better results from also feeding the data directly to the customers’ AI agents.

AI to Change the Economy Soon

The J.P. Morgan Private Bank has released an interesting report on their expectations for the U.S. economy. (60-page PDF)

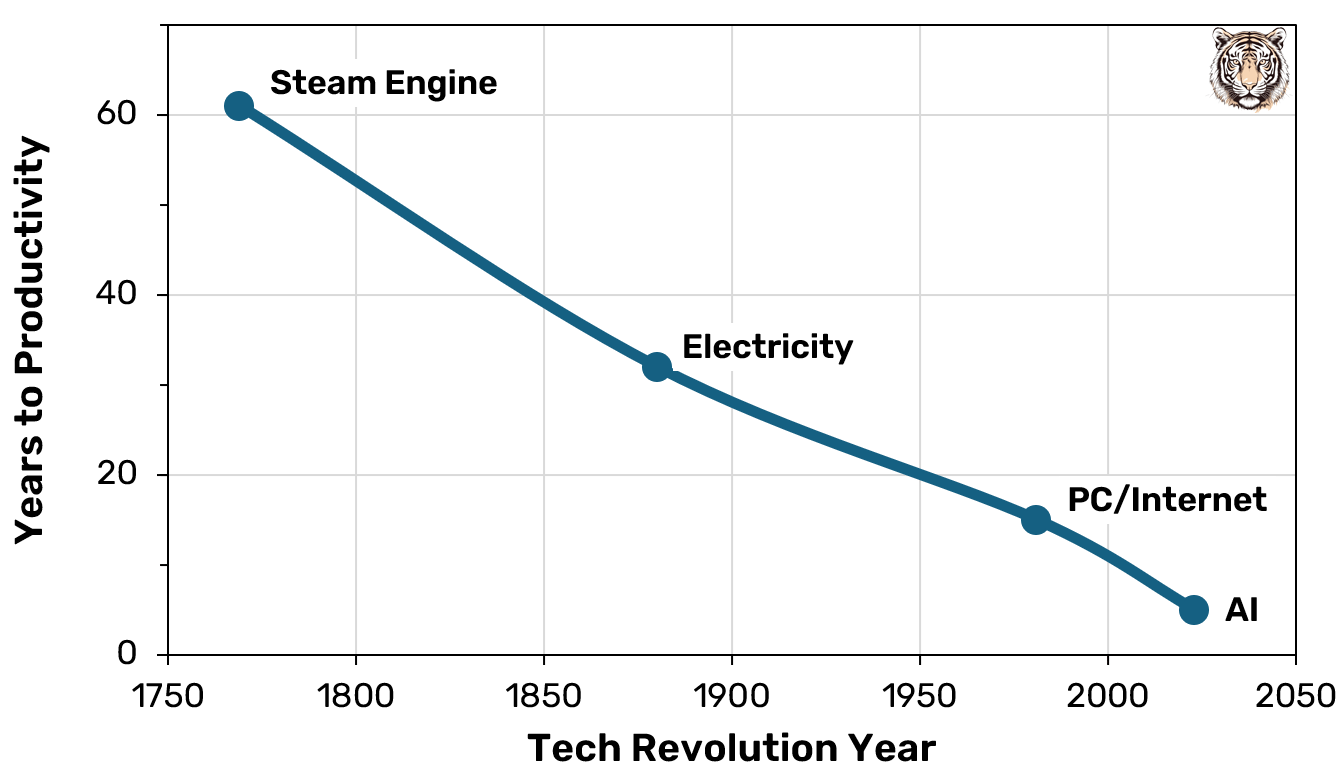

One chart shows the time from the introduction of a major innovation until it created major productivity growth in the economy:

Steam engine: 61 years, starting in 1769

Electricity: 32 years, starting in 1880

PC and Internet: 15 years, starting in 1981

AI: 7 years, starting in 2023 (the year of GPT-4, which was the first good AI)

Each technology revolution takes society to higher levels of productivity and therefore better living standards. However, it takes time for innovation to diffuse widely enough to realize these gains. The delay between invention and productivity is getting shorter for each generation. (Ideogram)

There is almost a linear trend between the year a major innovation happened and the time it takes the economy to bring it to profitability. We’re getting better at tech diffusion.

In other words, J.P. Morgan does not expect AI to really improve productivity across the economy until 2030. (They acknowledge pockets of improvements that are already happening, but technology diffusion is slow, even for something as revolutionary as AI.)

If we were stuck with current levels of AI quality, this prediction seems reasonable. In fact, it does take years for companies (especially big ones) to change their work processes to fully integrate the capabilities of a major new technology. Using electricity as a case study, factories needed to be completely rethought to distribute motors to every workstation instead of the centralization required by steam engines. A few companies possibly had sufficiently innovative factory managers to do this quickly. Still, most companies were satisfied for decades by the proven steam tech that already ran their factory floors and didn’t want to invest a fortune in building new electricity-powered factories.

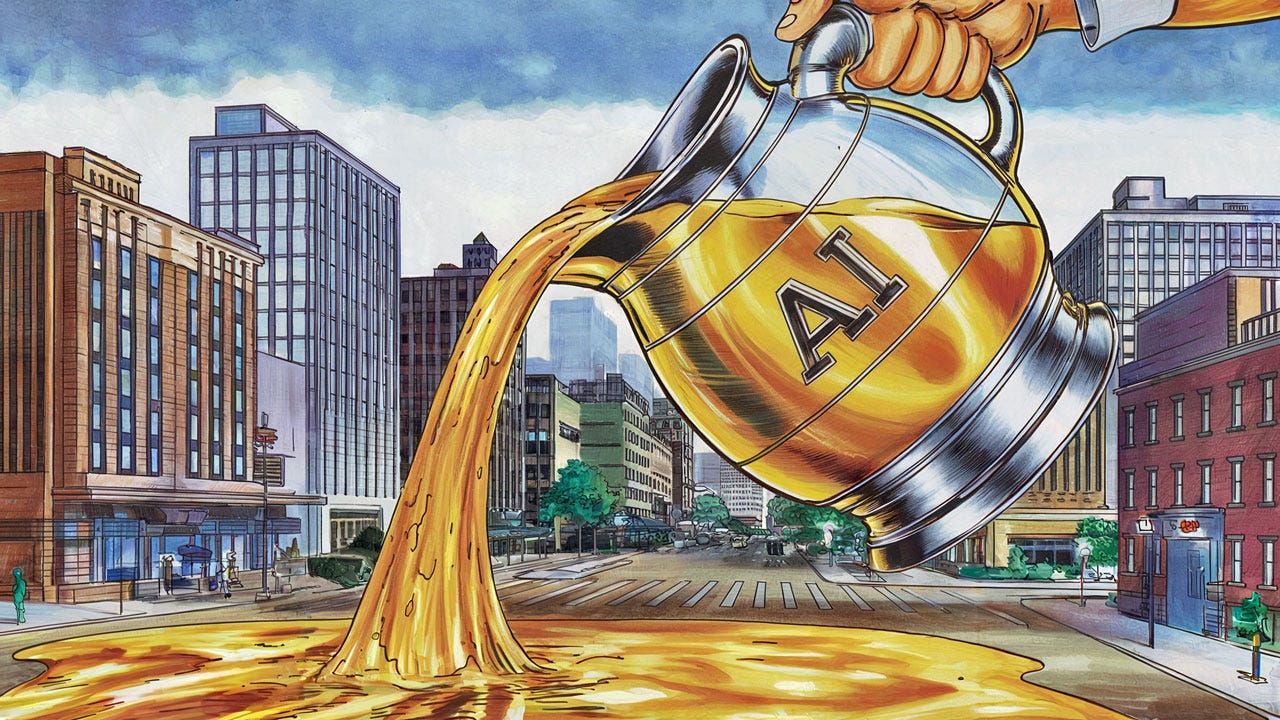

The AI revolution is clearly here. But when will it turn into immense productivity gains? (Midjourney)

However, AI is not a steady target that needs to be diffused. We expect extreme acceleration in AI capabilities for at least another decade. Current AI is like a smart high school graduate and is best thought of as an eager but unskilled intern in a professional business context. The next generation is expected to launch in late 2024 or early 2025 and will be like an entry-level business professional with a bachelor’s degree. Two generations down the road (expected to happen around 2028), AI will have Ph.D. level skills — expect that AI will be practical and not academic. By the early 2030s we’ll get ASI (artificial super-intelligence), where AI exceeds the skills of even the smartest human.

However, we don’t need to wait for ASI. The best business results come from an AI-human synergy where the combination of the two forms of intelligence is more potent than either alone. As early as 2025, AI will graduate from eager interns to well-trained junior staff, meaning that its potential for productivity improvements will skyrocket.

Simply having better AI-human symbiants available by 2025 doesn’t need that all companies will use them. Nor does it mean that many companies will have figured out how to restructure their work processes to best utilize this new potential. However, AI is great at ideation, and next-generation AI will be even better. This improved AI will help enlightened companies ideate the best new workflows and organizational structures.

I agree with J.P. Morgan that AI will diffuse through the economy faster than previous tech revolutions and that it will start to supercharge company performance faster than earlier case studies. I disagree with them that we must wait until 2030 to see these results. 2028 is a better estimate.

We can pour AI gold over a business district, but it’s a high-viscosity liquid, so it takes time to diffuse, particularly to the largest and most innovation-resistant companies. (Ideogram)

AI Predictions

After this prediction of AI impacting the economy faster than the previous tech revolutions, let’s review the general topic of predicting AI. Ahmet Acar from the Attain Institute in Nairobi, Kenya collected 1,406 predictions about AI from various notables made between 1949 (John von Neumann) to 2024 (Sam Altman and many others).

Famously, “It’s Difficult to Make Predictions, Especially About the Future.” This saying is so famous (and true) that it has been ascribed to many people, including Niels Bohr, Sam Goldwyn, Robert Storm Petersen, and Yogi Berra. (However, the earliest documented source is a debate in the Danish parliament in 1937.)

The specifics of these many predictions have already turned out to be wrong in many cases, but it’s interesting to note certain insights that appear repeatedly. For example, in 1951, British computer pioneer (and face of the £50 note) Alan Turing said “There would be great opposition from the intellectuals who were afraid of being put out of a job. […] There would be no question of the machines dying, and they would be able to converse with each other to sharpen their wits.” The first of these insights has already been proven right, with the profusion of decels and doomers. The second point, that AI will self-improve, leading to accelerating growth in AI capabilities has yet to happen, but I believe it’s very likely to happen.

Read through the predictions and see what nuggets you uncover.

Peering into the future of AI. (Midjourney)

Sam Altman On the Future of AI

Talk about predictions: Sam Altman (the head of OpenAI) published an essay about the future of AI, titled “The Intelligence Age.” I like his idea of dubbing the coming era the Intelligence Age, in analogy with earlier periods dominated by a certain technology, such as the Stone Age or the Industrial Age.

SamA’s essay doesn’t contain many new insights for those of us who have been thinking about AI for some time, but it’s a good overview that’s worth reading. We will experience unprecedented prosperity because of the AI scaling law: more compute equals more intelligence, meaning that we’ll be able to achieve increasingly amazing things with AI over the coming decade. He predicts superintelligence in “a few thousand days” or about 6-9 years from now. (I.e., around 2030, which is what most people have been saying, so no real news, other than he’s now on the record as well.)

One further point that’s also not new, but worth repeating, is that we ought to aim for all these new benefits to “into the hands of as many people as possible,” as SamA puts it. However, on current trends, AI will become more expensive, rather than cheaper, because super-AI requires electricity and the required nuclear power plants are not being built. (Yes, the U.S. will soon reopen a few mothballed old nuclear plants, and while that’ll help in the short term, it’s drop in the bucket.)

Sometime between 2030 and 2033, superintelligent AI will earn a place at the table next to top-performing humans like Einstein (science), Shakespeare (art), and Cleopatra (manipulation). It’s empirically proven that this level of superintelligence is possible, because bio-brains reach it every century. The question is whether even higher levels of superintelligence are possible, once thinking isn’t restricted to fitting within a breadbox. I think yes. (Ideogram)

AI UX Job

ElevenLabs is hiring a product designer. They also have openings for a design engineer, a brand designer, and a motion designer. ElevenLabs is an AI voice platform, so I don’t know why they need a full-time motion designer. Unless they’re moving into avatars, which might be a logical next product after voice generation. Their current product is to generate high-quality speech in 32 languages for applications like audiobooks, video voiceovers, and advertising.

ElevenLabs is a leading AI company for voice generation. It’s hiring a product designer. Go ahead and apply. (Midjourney)

About the Author

Jakob Nielsen, Ph.D., is a usability pioneer with 41 years experience in UX and the Founder of UX Tigers. He founded the discount usability movement for fast and cheap iterative design, including heuristic evaluation and the 10 usability heuristics. He formulated the eponymous Jakob’s Law of the Internet User Experience. Named “the king of usability” by Internet Magazine, “the guru of Web page usability” by The New York Times, and “the next best thing to a true time machine” by USA Today.

Previously, Dr. Nielsen was a Sun Microsystems Distinguished Engineer and a Member of Research Staff at Bell Communications Research, the branch of Bell Labs owned by the Regional Bell Operating Companies. He is the author of 8 books, including the best-selling Designing Web Usability: The Practice of Simplicity (published in 22 languages), the foundational Usability Engineering (27,537 citations in Google Scholar), and the pioneering Hypertext and Hypermedia (published two years before the Web launched).

Dr. Nielsen holds 79 United States patents, mainly on making the Internet easier to use. He received the Lifetime Achievement Award for Human–Computer Interaction Practice from ACM SIGCHI and was named a “Titan of Human Factors” by the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society.

· Subscribe to Jakob’s newsletter to get the full text of new articles emailed to you as soon as they are published.

· Read: article about Jakob Nielsen’s career in UX

· Watch: Jakob Nielsen’s 41 years in UX (8 min. video)

tl;dr

I suspect we have less than 2yrs before UIs will start to be absorbed by our own personal AIs. Most products/services/tools won't exist, and most UX research roles won't exist as we know them today.

In my mind, UI will be absorbed by everyone's personal AI. We'll all just ask our AI to perform the tasks we typically perform through UI. If I use my bank's website today, I'll tell my AI to do it. I want the latest news, I ask my AI. Need to find and order a gift, my AI can suggest gift ideas and place the order. Meaning, most of the products and services online today will be gone, they won't exist.

Platforms which will remain will likely integrate with our AI with something akin to an API, allowing everyone's AI to communicate between them and with products, services, tools, and government. Those platforms will largely be a scaffolding or skeleton upon which AIs will use to perform tasks. Should there be a need for a UI solution, our AI can build a unique, one-off, perfectly personalised product in seconds. We won't be needed...

If the need for a browser, or whatever replaces the browser, it will be for human to human communication (chat, audio & video calls, forums) , entertainment (video, gambling, eSports), education, enterprise & government platforms, and little else.

I suspect all of this will start taking share within 2 years. Last year I predicted we might see 85% of UX research jobs, as we know them today, will be gone by mid-2025. Now I think it may take until the end of 2025 but either way most of us have less than a year in our profession.

Great read, especially the thoughts on "human-targeted UI design" vs. "machine-targeted API design".